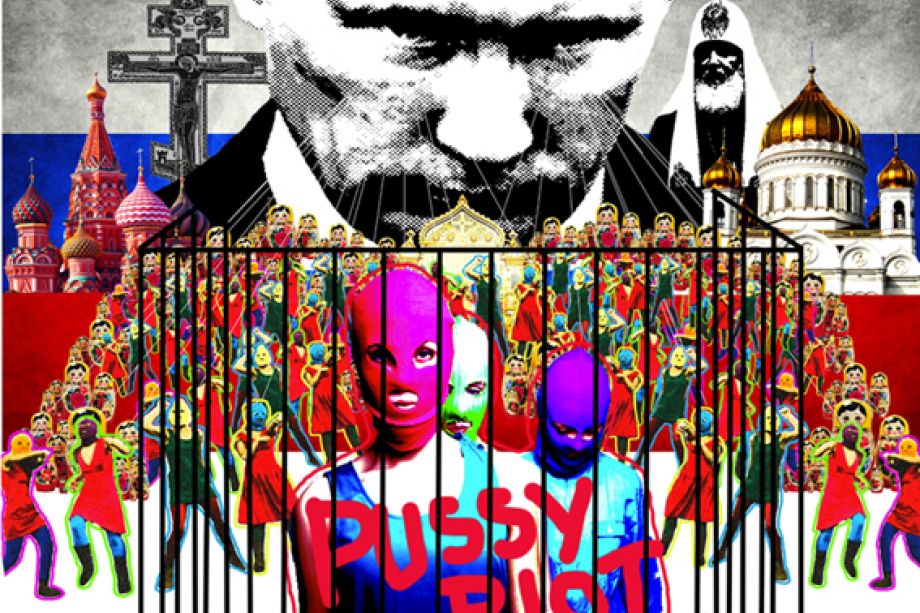

Gulag is alive and well in Mordovia

Everyone knows who the members of Pussy Riot are, and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova’s letter from the prison camp IK-14 was published worldwide. However, the Stalinist legacy in Russian prisons is still a shameful secret, according Tolokonnikova's husband, Pyotr Verzilov, who in this text calls for international solidarity.

On 23 September 2013 the whole world awakened to Nadezhda Tolokonnikova’s battle with the dragons of the Russian federal penitentiary system. Nadya, as we all call Nadezhda, wrote a heart-breaking and powerful letter, which described for Russia as well as for people around the planet the situation that she witnessed in the prison known as IK-14, where she was incarcerated for the whole of last year. The IK-14 prison is one of more than 20 prison facilities tightly clustered in the western corner of Mordovia, 500 kilometres from Moscow. Together they comprise a system known by a nickname, ‘Mordovlag’, which makes any Russian familiar with our history shiver. Even in Western ears Mordovlag sounds like a term straight from Solzhenitsyn’s books, and it essentially is a rudimentary piece of Stalin’s prison system, the Gulag. Within 50 kilometres along a south-north axis these 20 prisons house an astonishing population of over 20,000 incarcerated people. Less than 50,000 people live around these camps, which means that no one who was born and grew up in the western corner of Mordovia north of the town of Zuboba Polyana can imagine any other employment opportunities aside from becoming a guard, an inspector, a letter censor, a prison brigade commander or some other kind of a prison officer inside the notorious Mordovlag.

This social situation is twisted and bizarre enough in itself, but the full emotional and historical importance of the Mordovian prison system is felt when you realise that after the late 1960s, when the Soviet government was closing most Gulag prisons around the USSR, it decided to keep one prison system open for political prisoners. Thus Mordovlag became the only island of the Gulag archipelago which prevailed. There are many sayings among prisoners who served out their sentences in one of these prisons in the Mordovlag: “If you’ve been to a prison camp in Mordovia, hell will seem like a rather elegant resort”. “Don’t say you’ve done time until you’ve been sent to Mordovia”, etc. Families living around these prison camps have for generations—since the mid 1920s—worked in the Mordovlag and considered penitentiary service to be their family profession. This has led to a special degree of brutality among these officers, since the locals, who for generations had treated the prisoners like cattle, developed strong family traditions of working with internees. The brutal traditions passed from grandfather to father to son and became infamous across the Soviet Union, with most prison officials in the Mordovian prison system of the belief that they are still living in a Soviet-style reality, frozen somewhere around the mid-1970s. This is precisely the reason why Nadya’s letter about the conditions of Mordovian prisons shocked millions of Russians. People thought that the Gulag had long since vanished, which you could believe from reading a school course in history and literature—but Nadya’s letter made them realise that inside Mordovian prisons, 2013 is no different from 1975. Shifts of 18 hours at the sewing factory, food so disgusting you can barely taste it no matter how hungry you are, constant physical and psychological abuse, absence of the most basic sanitary necessities—this is a 21st century reality in a women’s prison in Mordovia, which millions of people have found still exists, in their own country.

“You should know that when it comes to politics, I am a Stalinist,” is something Colonel Kulagin, one of the head administrators at the IK-14 prison, likes to repeat. He became Nadya’s personal enemy and continued to threaten her to death until this triggered Nadya’s hunger strike and public appeals in support of her. Colonel Kulagin and his colleagues, who run the Mordovian prison system, have been allowed to act like they do because they meet very little resistance when they treat prisoners as they do, like cattle that they think deserve exactly this kind of treatment from courts all over Russia.

There are however shining examples of prisoner resistance, examples that have pointed out a path to change in these facilities, and the brightest of them all comes from that old Soviet prison reality, where the dignity of political prisoners was put to the ultimate test. In 1968 a famous Soviet dissident and writer, Alexander Ginzburg, who was serving his second long prison sentence in Mordovia, declared a hunger strike to protest against the prison administration’s refusal to allow him to marry his fiancée Arina. Under Soviet law, only officially registered spouses had the right to visit their incarcerated significant other, so Alexander was not able to see Arina for two years following his arrest, as the KGB arrested him a few days before their wedding. For many months he tried to get the prison bosses to allow him to marry Arina in prison, but received constant rejections. He declared a hunger strike and a miracle of solidarity took place inside the prison: a huge number of political prisoners in his camp, people with extremely different backgrounds—Ukrainian and Baltic nationalists, priests and Marxists, communists and monarchists—all united and declared a hunger strike with the sole goal of fighting for the right of Alexander Ginzburg to marry his fiancée Arina. News of this hunger strike on a scale previously unheard of leaked out from the prison and reached foreign radio talk shows, to the outrage of the Soviet authorities. After an amazing 27 days of collective hunger strike Alexander and Arina were allowed to marry. At their marriage ceremony in the prison Alexander met Arina with a huge bouquet of beautiful flowers, which had been collected for him by a squad of political prisoners, who were able to put their political views aside while fighting for one person’s right to dignity.

Forty-five years later, in the autumn of 2013, when Nadya declared her hunger strike in a prison nearby Ginzburg’s old camp, she received overwhelming support from people in Russia and all over the world. Her letter became the most widely read Russian text in many years and brought astonishing attention to conditions inside Russia’s penitentiary system.

The prison system tried to fight back and placed Nadya in two-month-long isolation, but the female prisoners in camp IK-14 were courageous enough to prove to a Special Presidential Commission sent to investigate that every word in Nadya’s letter was true. For these women this was a heroic move, as they had long prison terms ahead of them. By supporting Nadya they were subjecting themselves to retributions from the prison administration, but they felt that telling the truth was more important than possible future punishment. And punished they were: one woman spent several weeks inside a special isolation cell, another girl had her phone calls and privileges of contact with her family taken away, while a third was banned from receiving food parcels.

Now it is our turn to protect these prisoners, who are brave enough to stand up for their rights and to take the next move to change the situation in prisons in Mordovia and all over Russia. For this purpose, Nadya and another incarcerated member of Pussy Riot, Maria Alyokhina, together with their friends and a group of dedicated lawyers and human rights experts, are founding a special prison control NGO. This organisation, which will rely on crowdfunding from around the world, will be dedicated to purging the Stalinist legacy from Russia’s penitentiary system. People around the world will be able to contribute their resources and their attention to help run this NGO, and we hope that together we will be able to break the Mordovian prison traditions and inject a sense of human dignity among prisoners and the officers who control them.

We hope that, according to an amnesty which has just been announced in Russia, both Nadya and Maria will be set free before New Year’s Eve of 2014. We welcome people from around the world to help us in our fight to change Russia’s prisons and to once and for all turn another dark page in our country’s history.