Sounds of Peace

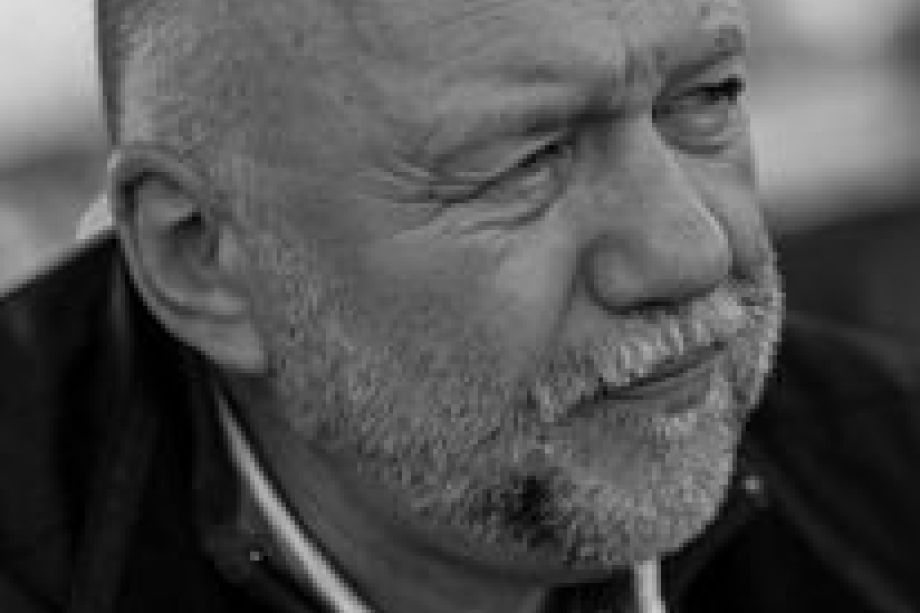

Former president of Ukrainian PEN Andrey Kurkov is one of the most translated Ukrainian writers. Kurkov received great international attention with the book Death and the Penguin. Since the beginning of the war, he has been busy participating in various conferences and festivals to speak for the Ukrainian cause. One year of war has passed, Kurkov shares his reflections on the role of poetry and literature during the time of war in Ukraine.

The sound of a Ukrainian word reaches the Atlantic coast of America before it can be turned into a printed word in Ukraine. Now everything is sound! Explosions, shots, cries of despair and words. Words that tell us about what is happening to us and our country. Words that tell the outside world about us. Words that help us share and deal with our pain.

Books, newspapers, and magazines require time. It is difficult for them to find time to be born in a country where printing houses and publishing houses were bombed back in the spring last year, and where readers, publishers, and writers have become soldiers at the front or volunteers, who rush to and from the front with help of any and every kind.

Traditionally, journalists tell the people of their country about the news. Writers and poets tell the whole world and future generations.

At San Francisco airport, I met Amelia Glaser and Yulia Ilchuk. They are excellent translators from the Ukrainian language and they were flying to Japan for a conference. They let me see an advance copy of a book in English by the Ukrainian poetess and Lviv University professor Galina Kruk. They are very happy that they were able to take this copy with them to show at Japanese universities. The collection of poetry is called “A Crash Course in Molotov Cocktails”. These poems have not yet been published in the original Ukrainian. They will be read first in Japan in English, then they will appear in American bookstores and fall into the hands of lovers of poetry, people with a refined sense of beauty.

One wonders, poems about the war, are they needed now in Ukraine? Of course, they are needed first and foremost in Ukraine, where they rescue, heal, and help people to survive. Poetry has become a huge engine for fundraising for the army. We saw this with the cult Ukrainian poet and prose writer Serhiy Zhadan. His poems are like gunshots! They charge, ignite, then freeze for a moment—long enough for several images of the poem to become planted in your thoughts and memory. During the war, people are very sensitive to precisely well chosen words, to intonation, and images.

I am sure that after the war, even more poetry will be read in Ukraine. Because many soldiers first heard poetry at the front. Because in poetry a single phrase can take you home or back to the past, to the peaceful past.

Traveling around Europe since March last year, I noticed how journalists and ordinary literature lovers listened to Ukrainian poets. I believe in the special ability of poets to choose one important word that can replace a dozen less important ones.

PEN members are fearlessly traveling close to the frontline to visit soldiers and civilians. They talk to everyone. They share their creative energy, but they also gather information about crimes against Ukrainian culture, committed by the Russian aggressor, and they help to restore cultural and social life in the recently liberated towns and villages. They write too, of course, chronicling every day of this war. They are important witnesses.

PEN keeps a close eye on Ukrainian political prisoners held by Russia, including Crimean Tartar activists and citizen journalists. The war has not made us forget about the unjust trials that target anyone who refuses to accept the Russian annexation of the peninsula.

No, I do not want to say that only poets can convey the drama of today’s Ukraine, the pain of a war that has destroyed the lives of millions of Ukrainians. No, this pain is transmitted to the world through many channels of art—prose, journalism, music, documentary, and feature films.

We try by all available means to share our experience and the truth about the war. Are we succeeding? Sometimes yes, sometimes not so much. But we, Ukrainian writers and poets, cannot but talk about Ukraine, about the war, about losses and hopes. Who knows our losses and our hopes better than we do? Who but us can tell the world about how Oleksandr Kislyuk, a professor and translator of classical antique literature, was shot dead in front of his house in Bucha in early March? Who knows better than the Ukrainian writer Victoria Amelina about the tragic fate of her colleague—author of books for children—Volodymyr Vakulenko, whose body could not be found for several months, and then, for another two months, could not be identified? He was buried a full eight months after his death. His thirteen books remain in Ukrainian literature. An number signifying bad luck.

Two bullets from a Makarov pistol were taken from Volodymyr’s body. Russian soldiers do not have pistols—only machine guns. Officers have pistols. Obviouslu, it was an execution. He was killed because he loved Ukraine and the Ukrainian language, Ukrainian culture, and Ukrainian history. They killed him because they saw strength in him. They killed him because he did not kneel before them, did not ask to be kept alive, and did not switch to Russian in conversation with them. This is how Russia kills, and has always killed, Ukrainian culture. In 1937–38, they shot Ukrainian writers, poets, playwrights, and scientists in the Karelian camp Sandarmokh or on Solovki Island, in the White Sea.

Dozens of Ukrainian poets, writers, translators, publishers, and journalists have perished in this war while others—Artem Chekh, Markiyan Kamysh, and Artem Chapai—have chosen to fight, not with a pen and notepad, but with a machine gun in their hands. They shoot and then write, and they shoot and then give Skype interviews. They are powerful voices of a country at war. Without them, the world would know less and empathize less strongly with our daily drama.

Over the past year, the outside world has learned a lot more about Ukraine. It has learned and continues to learn about Ukrainian culture and its literature. Diaries of Ukrainian refugees are being published all over Europe, books about the war are being published, and, of course, books about the history of Ukraine and the history of Russian-Ukrainian relations—about the three hundred years of Russia’s unceasing quest to assimilate Ukrainians and destroy Ukrainian culture. The time when nothing was known about Ukraine is over. People want to know more, but how can we learn to talk about something other than war? I don’t know. I cannot. Maybe if I were a poet it would be easier.

I sometimes close my eyes and listen to the past. I listen to and see pre-war Ukraine, which could always surprise and fascinate me. I see the town of Shargorod—an ancient Jewish town in the south of the Vinnytsia region, not so far from Moldova. There stands one of the oldest synagogues in Ukraine. It stands whitewashed and renovated, waiting for people interested in history. I remember Kamenetz-Podolsky with its deep canyon, along the bottom of which the Smotrych River flows. I remember Bakhmut—a place of dark mines, sparkling wine, and wartime atrocities old and new and Soledar—a salt mine turned into an enormous concert hall where the Donetsk Symphony Orchestra played Vivaldi.

I am sure that these cities will be rebuilt, revived, and that they will stand ready to share their riches, but the tragic year of 2022 will remain a bloody page in their history. When the locals are able to talk about this, they will be on their way to recovery. The only Swedish village in Ukraine, Zmievka, was liberated from the Russian army on November 15. At the entrance to the village, the sign gives the Swedish name—Gammalsvenskby. It too will be waiting for curious visitors and sympathizers. During the occupation, the Swedish flag was hidden out of sight, together with the Ukrainian one.

Ukraine has a rich history. The country has seen a great deal of tragedy. Now it has seen even more. Somebody must collect those tragedies and the tales of courage that guild them, write them down, and retell them. Today retelling is easier than printing. Peaceful sounds and words are precious.