Against the Grain: Writing Resistance

As a part of Banned Books Week, PEN/Opp publish an issue edited by the artist Shubigi Rao. The publication is made during a time when book banning is increasing globally in the wake of autocratisation and democratic decline. By inviting a chorus of voices – from Artsakh and Sarajevo to Manilla and the Correctional Institution for Women in Mandaluyong City – Shubigi Rao reminds us of the fact that writing, reading, translating, publishing and going against the grain are vital acts of resistance.

The publication is made in collaboration with Bildmuseet, Umeå University.

We are currently witnessing the rise of neo-fascism and totalitarian regimes colluding with oligarchs to destabilise social services, undermine public literacy, attack human rights and strip-mine entire ecosystems. It is more vital than ever to coalesce in opposition to these forces. To these mercenaries of control and exploitation, literature is always a threat as it can directly implicate, record, and personalise, and resist messages of dehumanisation and disinformation. This book includes guest writers from regions suffering genocide, on the fringes of 'empire', on the periphery and in the blindspots of the global news cycle. The writers featured are acutely aware of the collusion behind conflict and repression, and the ways to resist them through writing.

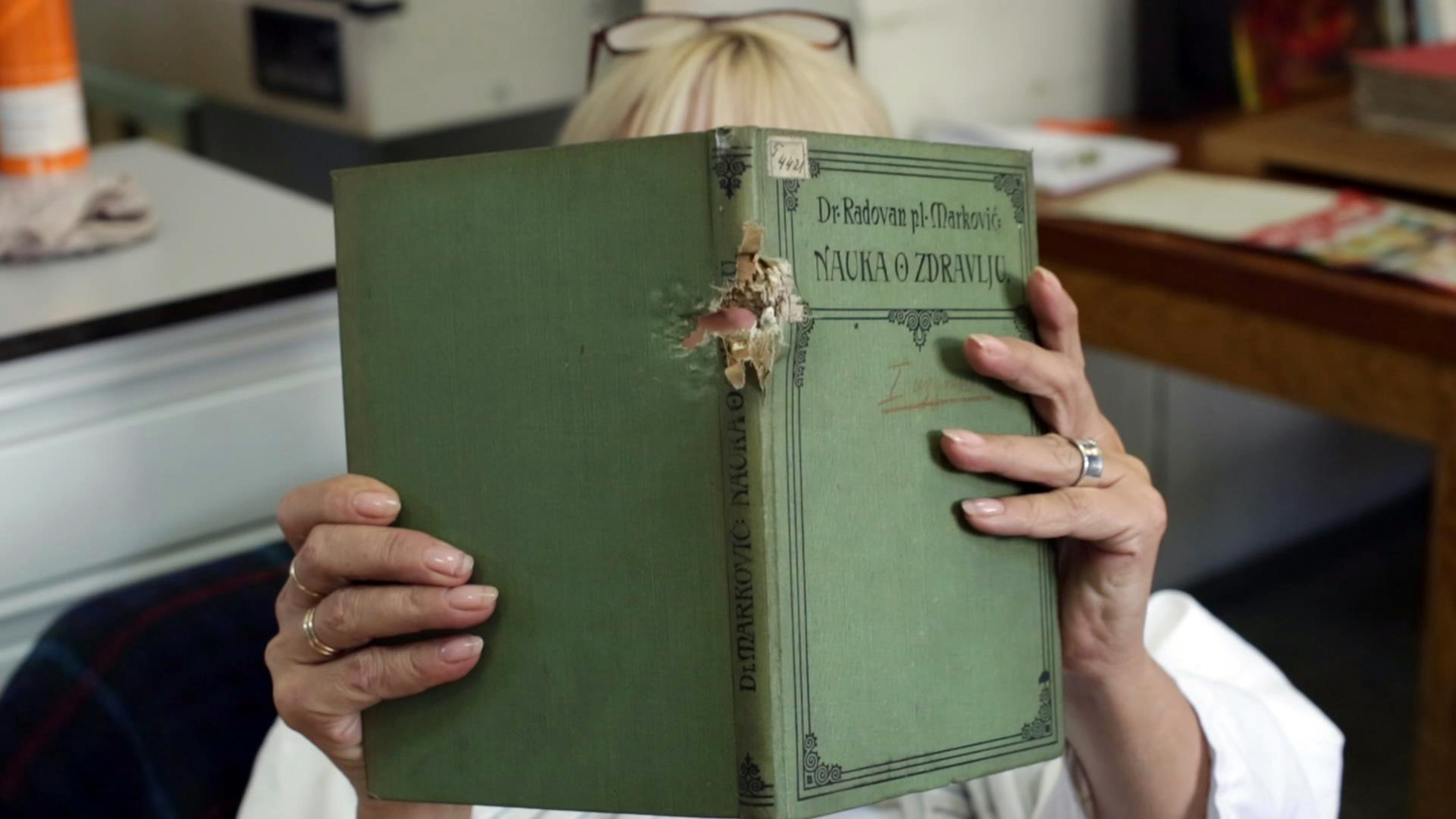

After all, to write a book is frequently an act of wilful disobedience against time, economics, domestic and personal demands, ideological, social and political strictures, and one’s invariable self-censoring voice. To read is an exercise of free will, and the communication between text/author/reader cannot be spied upon. To read is to defy millennia of illiteracy and intellectual servitude enforced through feudal, nationalist, economic, religious, sexist, racist, and other hegemonic rationalizations. To read then, is still as potent an act of resistance against every one of these forces, as it has always historically been. Many of the voices in this issue of PEN/Opp have faced varying levels of disenfranchisement, repression, injustice, displacement, transgenerational trauma, and imprisonment. The poems, essays, or interviews they have shared here reflect this, as well as embodying multiple strategies of resistance. The issue of PEN/Opp holds some of the voices that I was lucky enough to encounter during my long-term work about libraries under fire, censorship, and resistance to the forces that conspire to control and limit us.

It is tragic that the written word still needs to be defended, that it remains under fire. By its very nature, the printed text is a powerful form, an action even, and is feared and hated by repressive regimes that seek (always unsuccessfully) to completely control it. Sartre’s concept of Engaged Literature continues to be as necessary as its historical predecessors, with its ability to enable oppressed minority groups to identify and understand the mechanisms of resistance, and as action. Historical attempts to supplant the natural plurality of print (and the diversity of ideas, study and opinion it supports) with a single text have invariably ended in failure.

It is also because the story of the book is the story of our species, and at its most simplistic is also the story of our warring impulses to create and to destroy. While the book has been naturally associated with the former, it is perhaps noteworthy that when the latter impulse is exercised, it is often by those who venerate the idea of a singular Book. The tiresome libricides committed by fanatics from Savonarola to Boko Haram are because the plurality of print and literacy threaten their dogma. The book in this form is always singular, sacrosanct and final, and therefore of great appeal to the fearful, unironic and totalitarian mind. Arguably the most potent agent for change and reform (whether from the inhumane servility of feudalism, the scientific ignorance of orthodoxy, or the tyranny of systemic and generational poverty) has been that of mass print and literacy. In an ideal world, all human documents are egalitarian wherever there is literacy, and that illiteracy is the silencing of people. But the story of print isn’t simply one of technological innovation, market forces and geo-politics. The history of print is also the history of resistance, of radicalism and unorthodoxy, which is why it is constantly under attack. What do we make of moral panic haunting the headlines, perhaps as pervasive and as frightening in its shape-shifting, amorphous anonymity, its assumed neutrality? It is an effective outlet for the ‘concerned parent’, the outraged, the xenophobe, and other moral crusaders. The ‘values’ brigade (who always claim to speak on behalf of a larger, faceless silent public) can spearhead, and even participate gleefully, in acts of cultural proscription and destruction. As self-appointed guardians of order, morality and conformity, they can mobilize public opinion more effectively through sensationalism and media interest. Distilling a book to a single affront, rereading only in the vulgar, and that old mainstay of quoting out of context, are, after all, analogous to the art of locating the soundbite; particularly egregious because often they don’t read the text.

We can map the draconian measures taken against writing and writers across the world, in both despotic and ‘democratic’ nations. In The Philippines and Freedom of Expression Conchitina Cruz describes the attempted neoliberal takeover and militarization of universities, issues that are of particular global relevance in this moment, currently occurring in varying degrees in nations from the US to Japan. I am also indebted to Conchitina and Adam David for their work with women activists detained by the regime, whose writings are collated under The Long View: Compilation of Writing from Imprisoned Women Activists. Meanwhile in Staying Small, Faye Cura writes about the power of dissent, boycott, citizen protest and protest literature as resolute resistance. The militarization of language is another contemporary fallout of the media-saturated pornography of war, conflict, feuding factions, and is mirrored in the sound-bite dominated (shallow but very heated) debates that pass off as discourse on news channels. But this too has historical antecedents, for whenever a book was to be banned, an author discredited or punished, a library burnt, or funding cut, the justifications have invariably been couched in militaristic, oppositional terms, and with appeal to protecting either a deity, vague morality, or ambiguous but impressive-sounding security of state, family and society. The writing of Amanda Socorro Lacaba Echanis is vital in naming the forms of state repression and unjust incarceration, as much as it is also about persistence. We read this persistence, and the power of communal action, strategy-sharing and class struggle in the words of Mara Peralta and Mary Rose Ampoon, whose works are also testimonials against the militarized state that serves the interests of business and greed over those of its people.

The implications of normalizing militaristic action against public discourse, the terminology of simultaneous threat and display are impossible to ignore, as is the monetisation of every aspect of our existences. In an interview from 2017 for the Pulp project, Tomislav Medak speaks about shadow or pirate libraries that bypass the stranglehold of mercenary and predatory paywalling of knowledge, and how this creation and sustaining of a knowledge commons is necessary civil disobedience. It is telling though, that the notion of ‘illegality’ is rampant in so-called secular or democratic countries whenever we talk about civil disobedience. Acts of citizen resistance against injustice, wealth inequity, genocide complicity and systemic violence cannot be described, broadcast, lauded or reported fairly in mainstream media. It speaks volumes about the climate of fear and self-censorship under which custodians of knowledge operate. Worse, it describes how normalized we are becoming to the shaping of public discourse by the loudest, most extreme, hateful and intolerant voices, and how we accept excessive, outsize reactions as the natural outcome of any attempt to participate in a shared public arena.

This is another reason to look at covert and quiet subversive power of resistance in writing that begins in the home, in families and in our connection to soil, our forests, our bio-regions, our terrains both terrestrial and imagined. Here, Empty Fields by Gina Srmabekian is a fearless exploration of displacement after the Armenian genocide, an achingly poetic act of bravery, as is the poetry of both Nyree Abrahamian and Ruzanna Grigorian who variously describe the deep richness and vital necessity of love, of generational bonds, of genetic, cultural and literary memory, bonds that are damaged and severed by exile, genocide, and war. Selma Asotić too describes the terrain of transgenerational trauma and reckoning with the aftermath of war in 1990s Yugoslavia, in My Father’s Skin Looks Like the Surface of the Moon, along with the horror, shame and fury at the currently unfolding genocide of Palestinians, in After the Bombardment: for Beit Hanoun. These pieces sharply bring home to us the abstract discussion of mealymouthed politispeak, into the concrete of pain and rubble, into the sadly necessary reminder of the true costs of conflict.

But tyranny (in any form) is always temporary. Its weakness lies in its legitimacy being derived from the enforcement of a single doctrine or dogma. All it takes is a dissident or alternative idea to take root; paper will always trump rock. The singular will always breed acts of resistance in print, and often they take a quieter, more resilient form. Under the USSR, the Soviet bloc and Warsaw pact nations suffered the longest modern period of state censorship and oppression. Yet novel and eventually successful forms of counteraction like the samizdat (covertly printed or cheaply photocopies versions of banned literature) also marked this period. For instance, what the samizdat proves is the necessity of the human yearning for expression, and as an outlet, it serves a non-political purpose as well. Writers need to have their work read, intellectuals need debate and discourse, and when speech is dangerous because anyone could be an informer, the anonymous tract, pamphlet and text will do. Vladimir Bukovsky, Soviet dissident, writer and activist described the necessity and self-determinism at the heart of the samizdat as, ‘I myself create it, edit it, censor it, publish it, distribute it, and get imprisoned for it’. Writing, reading, publishing and going against the grain are vital acts of resistance. Scholars fleeing invasions, massacres and devastation have carried manuscripts and books with them, and this has triggered key intellectual and scientific flowerings in history. People have saved books as long as others have sought to destroy them, and so, despite the worst episodes of obliteration and genocide, a few (too few, sadly) texts have migrated and navigated lands, empires, political and religious states and systems, and somehow survived. With the looming Anglo-American invasion in 2003, and the Iraqi government denying her requests to evacuate books, Alia Muhammad Baker, chief librarian in the Al Basrah Central Library, Basra, enlisted the support of locals to smuggle out and eventually save seventy percent of the collection. She did this at great personal risk, smuggling them into a nearby restaurant where she hid them in a freezer and the kitchen. She saved 30,000 books. If there is one fact that emerges in the litany of loss and destruction, it is this: against the outsize forces of repression and destruction, every action, no matter how small, is a practical demonstration of an ideal commons, of a plurality that will eventually, always persist.

/Shubigi Rao

-Portions of this text have previously appeared in ‘Pulp: A Short Biography of the Banished Book, Vol I of V’, by Shubigi Rao, 2016.