Editorial

How could we understand what is actually “taking place?”

A well-known, if slightly worn quote by the Swedish historian and poet Erik Gustaf Geijer sum up the mission of any scientific endeavour: “to see what takes place in what seem to be happening.” As one scans the world’s current political landscape—one that is rapidly changing—it is easy to wish for a ‘grand theory’ that could precisely explain what is taking place in what seem to be happening. On the one hand, democratic rebellion against corrupt regimes, and on the other, new threats of terror directed towards the opposition, and towards writers and journalists.

The “Arab spring” is already a concept that invokes scepticism in some circles. Has this spring really offered a democratic opening? Simultaneously, a dictatorship like the one in Burma is at least beginning to mime a perestrojka. And, at the time of writing, demonstrations are taking place in the streets of Moscow in protest against election results that are being contested by the opposition. In Hungary a development towards a more restricted freedom of speech continues alongside growing racist tendencies that the representatives of the regime are doing nothing in order to stave.

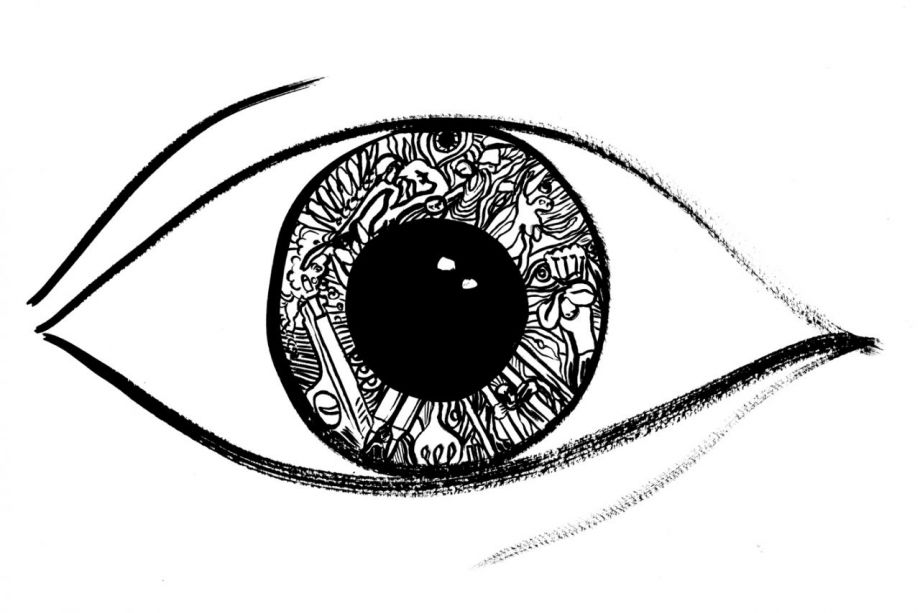

How could we then possibly understand what is actually “taking place?” An eagle’s perspective—one we often come across in media—can be highly misrepresentative. From this perspective one often sees only the map but not human beings. I am not implying any critique of media here; to summarise and to generalise is often the first step in the understanding of any event. However, in order to pass beyond these generalisations it is necessary also to listen to real peoples’ individual voices—to their narrations of factual experiences, which incorporate things that do not fit neatly into any simple truths.

This is precisely what PEN/Opp aspires to do. In this our third edition, Fawzia Assaad reports from Egypt on the role of the Christian minority during the spring uprising—a Christian minority that today is finding itself increasingly circumscribed. Oksana Chelysheva, a Russian journalist who since many years is living in exile, writes about how children become victims of the forces that are trying to silence the voices of the opposition. Also, several Hungarian writers give their views on developments that are currently re-shaping a democracy in the centre of Europe—a country where it is once again becoming accepted to harass Jews and Romani. Lastly, we also present some examples of forbidden Vietnamese poetry.

We have no ‘grand theory’ of explanation. But PEN does have a network of writers all around the world. These writers want us to listen to their narratives about what is taking place in what seem to be happening. Here we present some of the voices from this period of quick historical change; voices that we otherwise might never have heard.