Fathy Ghabin: Inevitable Binaries

Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will

– Gramsci

One of the central issues in radical thought aimed at changing reality is the relationship between thought and action. This is especially true when it comes to themes of misery and pessimism versus hope and optimism. Any revolutionary school of thought must understand from the outset the complexities of reality and the difficulties of changing it.

It's essential to realize that individuals cannot single-handedly confront the institutions consisting of structures they cannot dismantle without being a part of everything that contains them. It's not just about the place one occupies in society or community; it's about the energy one brings to the fight. Is it an energy that understands the complexity of reality and the difficulty of change, or is it a naive belief that hope will fulfill their desires at the nearest crossroads?

For artist Fathy Ghabin, man, whether alone or in a group, is the primary focus. He zooms in on individuals as masses that produce life and meaning, cultivate the earth, resist oppression, and raise future generations through their daily practices.

Ghabin's paintings depict Palestinians in their natural state, free from politics, cities, or their surroundings. He portrays the Palestinian farmer, who understands the meaning of resistance, individually and collectively. The farmer loves his land and identifies with it, experiencing sadness at times and bravery at others. Ghabin captures the Palestinian Heideggerian quest for life, away from the world of technology, seeking a sense of innocence through attachment to the land and separation from modern life in all its forms.

Ghabin himself embodies this Palestinian way of life. He learned art through instinct, as Socrates learned philosophy and Beethoven learned music, without attending an art school in Paris or Europe. He practices painting by hand, experiencing it directly, tangibly, and in reality, without the guidance of teachers or modern or traditional schools of art. This Palestinian way of life is direct and comes from staring long enough into the mirror of reality.

His paintings seem to come from another world, in which Palestinians are in their original form. Before the occupation, before the mandates, before the need to ask questions about the self and the other. A world where the self was present and ready. Something else that stands out in Ghabin’s work is his keenness to include some context.

Ghabin’s art can be understood by looking at the world, in which its roots lie. Behind every painting, there is a past that can add a new meaning to it. This meaning can be inseparable from it, but hiding. In each art collection, you find clear features, such as a specific body movement, that hints at a certain context or timeframe. We can consider this context the backyard of Ghabin’s art pieces.

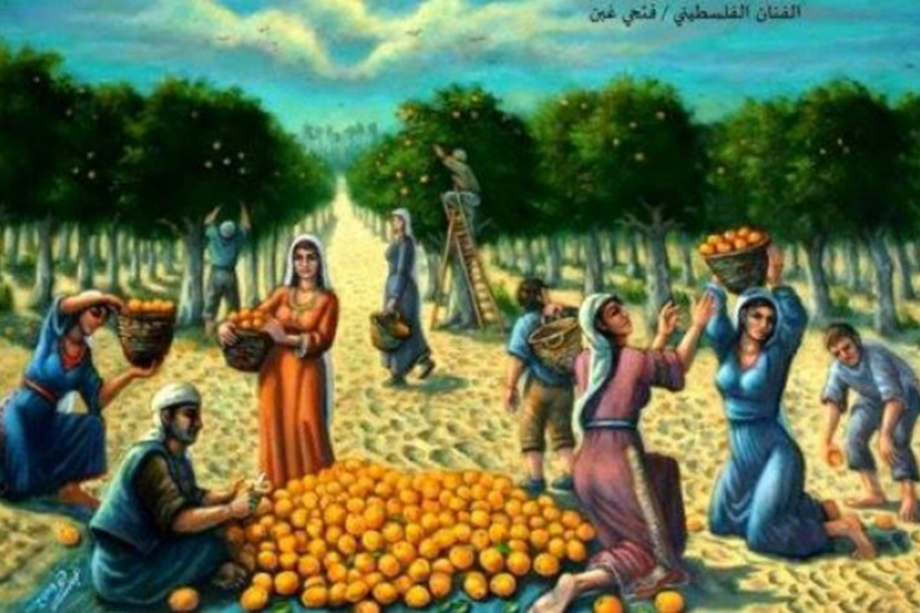

Ghabin's world is not monolithic. It is always about Palestinian identity, but in its plural and diverse sense. In the painting below, you find farmers picking oranges as if they were at a party. Some gathering in a circle, old men on trees, women carrying oranges, and bodies dancing. It is a depiction of a purely festive Palestinian ritual.

Ghabin's paintings are characterized by bringing together multiple personalities. In each painting, there is one or more characters stationed in one of the corners of the painting. Their features are always clear and calm, not angry or miserable. These typical Palestinian features highlight a certain idea that Palestinians know well; life goes on no matter what.

On a personal level, I found the fading expressions an intuitive image of every Palestinian who knows how to keep going despite all the psychological trauma they’ve suffered. The inevitability of life means that everything can be put on the sidelines until work, in this case farming, is finished.

This is a daily experience understood by every Palestinian who went to school, university, or work in the morning after their home was stormed, threatened, or even bombed. The duality of hope and despair fails here. Because despair is not an option and hope seems like a luxury. We can see Gramsci's Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will here in how the Palestinins live. Reality is open to all the bad possibilities experienced in the past, but this does not affect the will, which still tries to open new horizons.

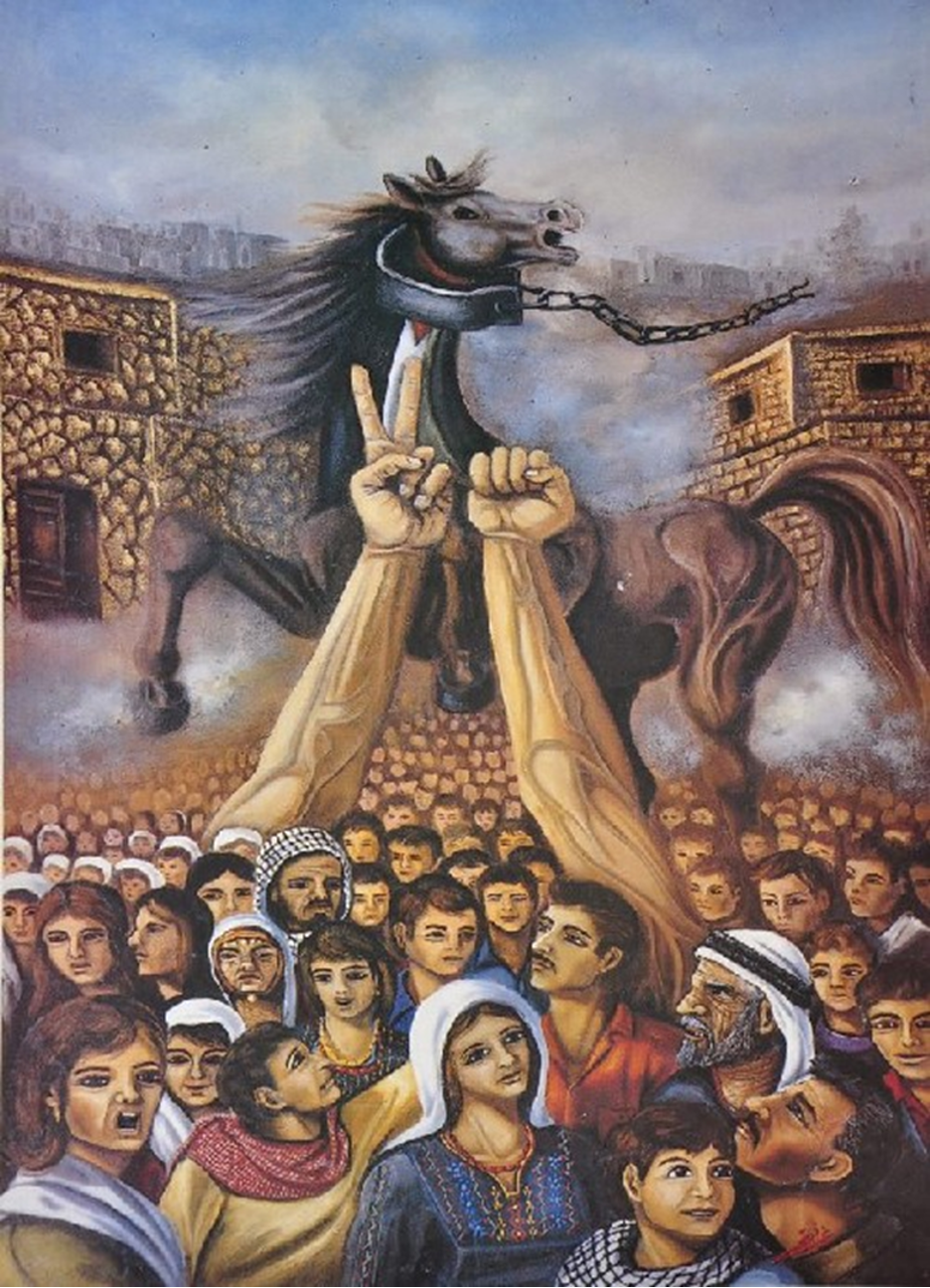

Will, in this context, also refers to revolution, where one has to overcome the despair of the will that prevents change. The paintings also display the pessimism of the intellect, which is apparent in the features of most of Ghabin's characters. It is a pessimism that is rooted in the reality that Palestinians experience every day.

For Gramsci, this slogan refers to a person's ability to fight with systems and institutions that are stronger and more organized. When the odds aren’t in their favor, but their will fights on. Despite their awareness of the negative possibilities. This duality can be seen in Ghabin’s paintings– although the features may indicate despair or pessimism, the will or action represented indicates optimism and hope.

This is a binary around which not only the Palestinians revolve, but anyone who tries to change reality or dreams of a different one. A group always forms in every struggle. This seems self-evident in reality, because no change takes place without a single collective working together to defy the possibilities. In contrast, every character who walks alone or works in isolation ends up in despair.

It’s impossible here to overlook the essential presence of women in the paintings. They take on multiple roles– sometimes baking bread for their children as they take care of them, other times joining protests. The presence of women in Ghabin’s paintings tends to be more highlighted than the presence of men in terms of features and roles.

Women play more than the traditional roles in his paintings. He depicts them in roles traditionally played by men in conservative societies. There is a feminist aspect about the way in which he depicts them. Firstly, his highlighting of them raises their issue, but also the features of their grieving feminine faces tell the story of a past.

Ghabin's paintings are still a window to reality. They can expand to represent the suffering of the Palestinian people, whether it be their loss of meaning or lack of options. Returning to the old Palestinian in his “natural” state is not an option here. The damage has been done, politics has been set, and the reality has changed. But it’s possible for a Palestinian or Ghabin’s paintings to transcend the confinement of the traditional and the old. They can do this not by accepting reality and surrendering to it, but by proceeding from reality to change it, or even turn it upside down.