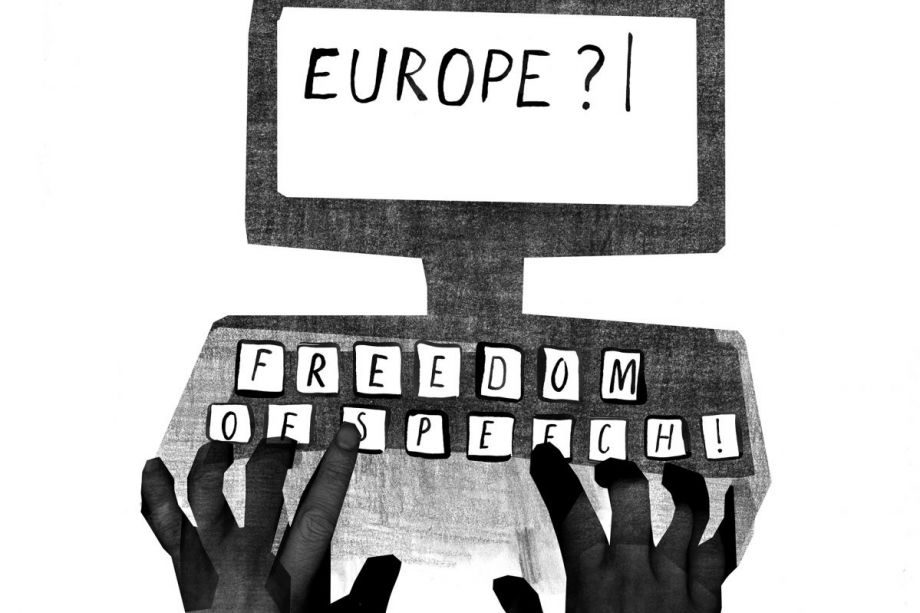

It is easy to sound apocalyptic when discussing the directions that the freedom of speech is taking in the world

Year after year the organizations that globally monitor the freedom of speech and of the press reach the same depressing result: in the last decades there has been a gradual erosion of free speech. Freedom House claim that on the web, globally, the freedom of expression and information has been curtailed for the fourth year consecutively. Concerning the free press in Europe the organisation drily points out that “press freedom faces threats in a number of states.”

In the Reporters Without Borders’ world press freedom index there is a similar assessment: 2014 was a dark year that saw an escalating number of assaults against journalists and bloggers around the world. They claim, furthermore, that compared to other regions, Europe’s ratings fell steeply, the reason being that some countries have encountered severe problems during the year—problems that the EU system has been unable to control.

In these surveys Europe has long been rated “best in class.” But something has happened. Even here it is harder to uphold a free debating climate and the hindrances can differ between countries from direct threats to semi-censorship to self-censorship.

It is therefore hard to identify the fact that the freedom of expression in Europe is actually deteriorating, and that there are many factors threatening its existence. The outcome, however, is the same; ideologies and political excuses can vary but the fundaments remain: for the citizen it is becoming harder on a daily basis to find trustworthy information in the media, and it is evermore difficult for journalists and other writers to do their jobs properly, since they are also often subjected to personal threats. One might begin by mentioning the anti-demonstration laws in Spain—implemented without any protests from other European countries— then move on to mention the Hungarian government’s tightening grip over the country’s media and cultural institutions, and then to Ireland where the Blasphemy Law that criminalises blasphemy was strengthened in 2009, which is not what one might have expected at that time, to Russia where more and more journalists find themselves imprisoned for their words—Russia, a country that only competes with Turkey as concerns its numbers of imprisoned journalists. Also, there is Albania and the other Balkan nations where the persecution of journalists by organized crime is on the increase.

Then we have yet to mention the terror attacks in Paris and Copenhagen. No voices question society’s need to protect its citizens from this kind of ideological and religious terror, but, the follow-up question should concern the means used to combat such a development; security forces in Sweden and similar countries suggest digital surveillance as the best method to combat terror—while PEN American Center’s membership survey shows that digital surveillance has resulted in no less than thirty percent admitting that they more or less consciously practice self-censorship. The threats differ, but the results are similar: a shrinking public arena. This is at the heart of the problem: how small can the civic space of a country become for the country still to be called a democracy? Many people diminish “democracy” into merely a system where those in power are changed through majority rule, but they forget that for the citizenry to be able to make informed collective decisions they depend largely on having recourse to reliable sources from as many independent media as possible.

In this issue of PEN/Opp, Muharrem Erbey describes the situation in countries where leaders elected by the majority of the people attack the free media and circumscribe the public arena. He uses the term “democrature”—a concept once coined by Eduardo Galeano, a writer from Uruguay—in order to describe the situation in his home country. It is high time for PEN/Opp to focus on Europe, on the continent that all too often takes the freedom of expression for granted. There are strong reasons for us to make use of our freedom of speech and information in order to hinder it from being further limited. The same vital truth applies: democracy can only survive if it can defend itself without turning into its opposite. This is our current position.