The Myitkyina Library

The conflict in Myanmar concerns a struggle between democracy and dictatorship. After a decade characterized by a slow (and stagnating) process of democratization, the country has once more been thrown back into a dictatorship.

The media report on imprisoned dissidents, on writers forced to flee the country, and on a severely curtailed freedom of expression.

But for the person who wants to understand the complexity of the tragedy that has characterized Myanmar for decades, it is not merely about the more “traditional” threats to democracy and human rights.

It is also about understanding the country’s ethnic conflicts—and about the importance of language.

A few years ago, I visited a Christian college just outside of the city of Myitkyina in northern Myanmar.

The principal offered me green tea and showed me the premises. He was especially proud of the library that also contained some books in the local language Jingpho—the language of the Kachin people.

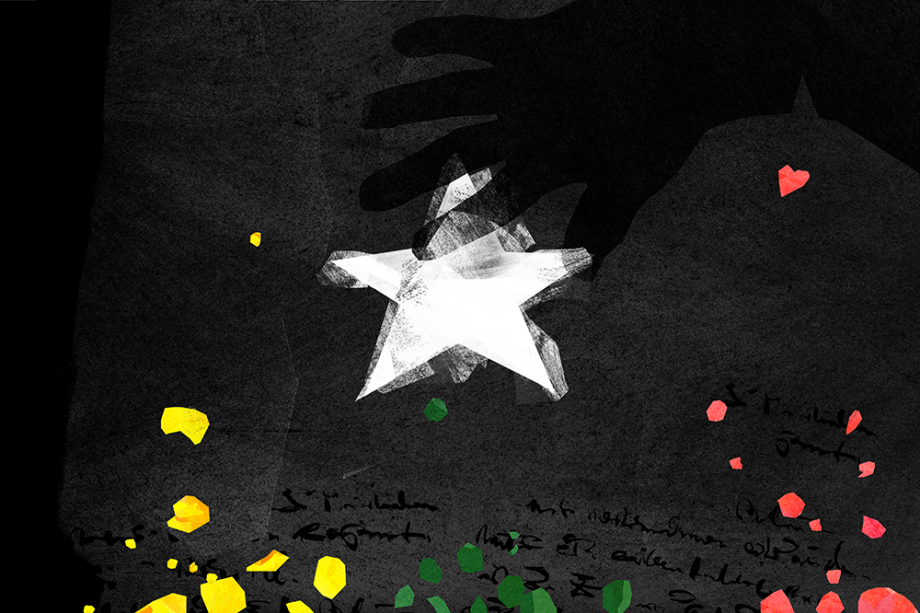

He drew his fingertips over this very small range of books and pointed to a picture on the wall. It depicted the Swedish-American missionary Ola Hanson. He was born in Åhus, and he came to northern Myanmar (then called Burma) in 1890 as a Baptist missionary. His mission was to Christianize the Kachin. At the time, the Kachin did not belong to any of the major world religions. However, they were terrified of being swallowed up by the Burmese Buddhist culture to the south of Kachin territory, or by a Chinese invasion from the north.

The Baptist missionaries were, of course, part of the colonial expansion in Southeast Asia, and there are many not so flattering things to say about this process. But for the Kachin, they offered an alternative to the identities of the regional powers.

Ola Hanson also had the task of creating a Jingpho orthography. The Kachin had their own spoken language, cultural memories, and traditions. An identity. But they had no written language.

It took him several years. He used the Latin alphabet and Swedish phonetics. While writing the first dictionary, he literally had to closely study people’s mouths to understand the exact way to pronounce a word, and then find the letter combinations that best would describe that particular word.

When he was done, he then spent thirty-five years translating the Bible. The Kachin consider Ola Hanson as their saviour. Without their own written language, without books in their mother tongue, they would have ceased to exist as a people.

Most Kachin speak both Burmese and some Chinese, but since they can read books and newspapers in their own language, they are rooted in their own history. The written word has empowered them.

This identity has also led the Kachin, like several other ethnic minorities in the country, to demand extensive autonomy. They want Myanmar to become a federation—an association of peoples and cultures where the centre is weak while the states are strong.

For several decades after World War II, the conflict in Myanmar has primarily touched on the issue of language. The military junta denied the minorities their rights, and an important aspect was language. They stopped the publication of all books and magazines in Jingpho, banned publishers and printers, and silenced writers and journalists. The minorities were meant to become “Burmanized” and “Buddhified.”

I often think of the small library in Myitkyina when I see the reports from Myanmar today. When the junta again has taken a firm grip on the country. When the short period of relative freedom has been turned into repression. When the war between the military and the ethnic minorities has flared up again in many places.

Then the struggle once more becomes two-sided: it is about the right to say and think what you want, the right to organize, and the right to make yourself eligible in political elections. But it is also about the right to one’s own language.

Jesper Bengtsson, President of Swedish PEN