Ola Larsmo: We need to know more about those who know everything about us

Two areas of unrest have dominated the news this past year: the growing humanitarian catastrophe in the wake of the civil war in Syria, and the insight that the ‘war against terrorism’ has given security services in the West carte blanche to monitor just about all digital communication between people—thereby monitoring us all.

We can imagine that we recognize the tragedy in Syria. It resembles similar conflicts in the past few decades where civilians with terrifying regularity have been turned into victims of slaughter. But here we are dealing with one of the world’s harshest dictatorships, one that first mainly met a growing but peaceful resistance, but whose violent retaliation against spreading protests among the citizens has led to an extensive terror against the country’s civilian population. Everyone who has tried to keep abreast with developments in the country is above all filled with feelings of frustration and powerlessness bordering on desperation.

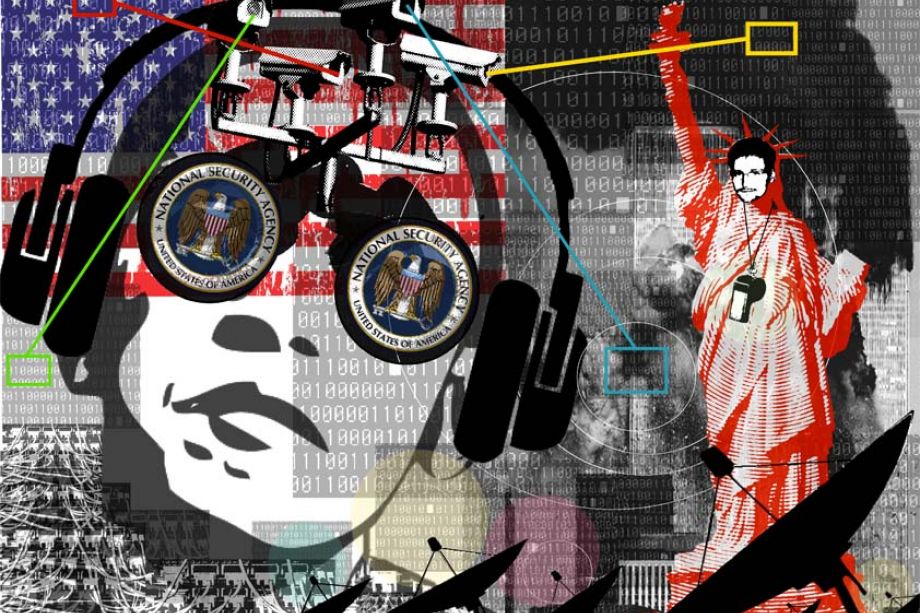

Digital surveillance—which we know in various forms such as Echelon, PRISM, and the Swedish FRA laws—is both familiar to us but also frighteningly new. Either we have been aware of it or not, since the Second World War we have lived in a surveillance society where garnered snippets of information have been political hard currency in the exchange of intelligence and espionage between countries and world power blocs. This is not new. What is partly new is instead the capacity to store digital information and to make digital searches made possible by today’s high-capacity technology. As Larry Siems says in his article here on this blog, this technology is like a time machine for the ruling powers: if you are caught resisting the regime, you can always be charted retrospectively, and those you have spoken or written to long before you knew that you would be regarded as a threat to those in power may be incriminated alongside you. Everyone is thereby turned into a suspect. So, if everyone is a suspect then is anyone really being threatened or victimised?

In itself, this technology is perhaps no threat. Instead, the threat lies in the slackening of legislation, in the loosening of peoples’ judicial integrity, and in the relaxation of the principles held by a country’s rule of law that follows from the former. It has become more important than ever to guard the guardians monitoring us—we simply need to know more about those who know evermore about us. Edward Snowden’s whistle blowing is therefore one of the most important contributions to democracy in these last few years.

The feelings of powerlessness I described above concerning the war in Syria are also a result of the increasingly accessible knowledge about developments in the country. For the second time in our modern age the deadly nerve gas sarin has been used on civilians. We know about it, we have seen its effects, but the world community remains paralyzed. Paradoxically, it is the same digital information technology that makes it possible for us to almost be in place to witness the developments in Syria. As Jasim Mohamed writes in his introduction to this issue’s block of newly written Syrian poetry: it is precisely this digital community that gives voice to the people living in the midst of the war in Syria. These people who in their texts bear witness to the war from within—something that the regular news agencies cannot possibly manage.

Since the start, it has been the aim of PEN/Opp to be a forum for voices such as these. We are grateful and honoured to be the channel for these writers—and we hope that they will be heard worldwide.