The Role of Exile in the Development of Modern Kurdish Literature

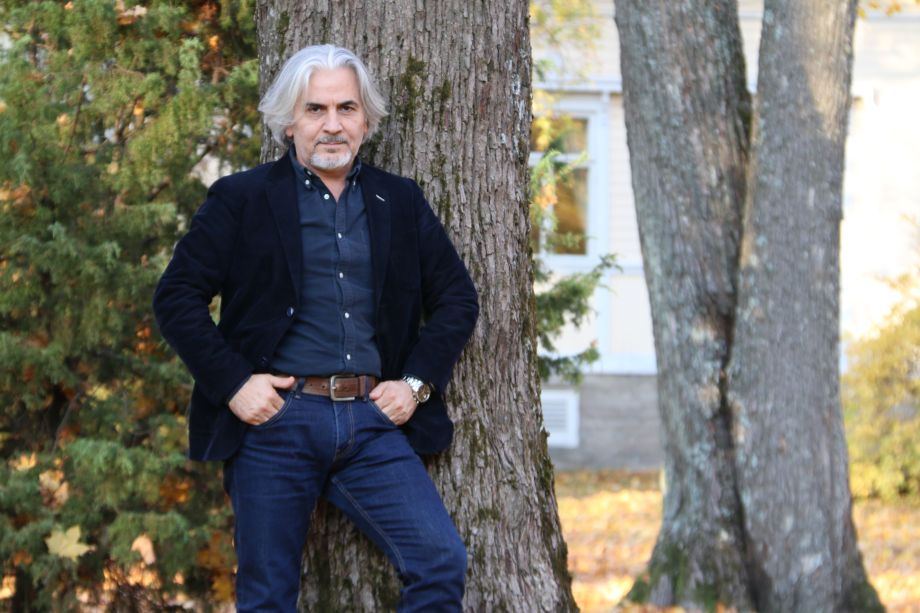

Firat Ceweri is the guest editor of this issue number "I see you in a glowing amber", a line from Kurdish poet Farhad Shakely's poem "Send an ember, one night, to see in my dreams".

He provides an introduction to the development of modern Kurdish literature where exile, in the absence of a Kurdish state, came to play a decisive role in the survival of Kurdish literature.

Firat Ceweri was born in the Kurdish part of Turkey. To be allowed to write freely he left Turkey in 1980 to settle down in Sweden. That same year he published his first book. Since then, he has been an active writer and has published forty titles: twenty of his own and twenty translations from Swedish to Kurdish. In 1992 he started the literary magazine Nûdem (New Times), which he kept going steadily for ten years. Nûdem has played a vital role in the development of Kurdish literature and has inspired many new writers. Firat Ceweri has also published a magazine with a focus on translations of world literature into Kurdish. Ceweri’s novels have been translated into several other languages. He has been a member of the board of Swedish PEN and Chair of the Writers in Exile Committee. In 2018 Firat Ceweri was awarded the Swedish Academy’s prize for translation of Swedish literature.

It is not possible to talk about Kurds without bringing in political aspects of their lives. Of course, this is due to the massacres they have been subjected to, the suffering they have endured, and that they have been forced into exile. The fact that the Kurdish language and its literature in periods has been forbidden has played an enormous role for how modern Kurdish literature has developed in exile.

After the forming of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, and after Turkey abandoned the Arabic alphabet for the Latin one in 1928, the Kurdish language and all Kurdish literature was banned. This banning was the basis of Kurdish journalism and modern Kurdish literature in exile.

In the history of Kurdish exile literature, there are three periods that have formed the modern Kurdish literature, which has made use of exile to shape a Kurdish identity and a cultural awareness. These periods are firstly, Kurdish literature in the Soviet Union, secondly, a period connected to the magazine Hawar, published in Damascus, and thirdly, the Kurdish literature created in exile in Sweden.

Kurds in the Soviet Union

The Kurds in the former Soviet Union originally came from the Turkish parts of Kurdistan. After WW1 and the Bolshevist Revolution, the borders of this territory were moved from Turkey into Russia. Following on the October Revolution and the founding of the Soviet Union, the Kurds were given the same cultural rights as other minorities in the Union. After the publication of the newspaper Ria Teze in 1930 in Soviet Armenia, while the political process of assimilation in Turkey was strong, the Kurdish language and its literature began to develop in Armenia. During this period, it was possible to study Kurdish in the Soviet Union, Kurdish schools were opened, textbooks were written, and Kurds were acknowledged as Kurds. Cultural and literary works were mainly to be found in Armenia, but soon Kurds in Georgia and Azerbaijan began to write and publish in Kurdish and during these years Kurdish literature flourished. Poems written early in the 1930s often had traits of folklore or were influenced by Kurdish folk beliefs, but these soon intertwined with motifs of class that all Soviet writers included to praise the Soviet system—the aim was to pay tribute to socialism to secure that the books received the support of the Communist Party.

However, Kurdish poetry written in the 30s, 40s and 50s in the Soviet Union inspired a wider interest in literature among the Kurds. The Kurds in the Soviet have also left a legacy of works within the fields of folklore, novels, short stories, research, linguistics, and drama. Although praise of the Soviet system is emphasised in these works, Kurdish customs, Kurdish roots, and Kurdish lifestyles are still portrayed. The spreading of such works though was inhibited by the Cyrillic alphabet. What is more, there were restrictions both within the Soviet system and the Turkish system, so this new literature failed to reach most Kurds. Thus, Kurds in Kurdistan were oblivious to the cultural, intellectual, and literary development that was taking place. After the Soviet Union’s collapse, these Kurdish writers and intellectuals went into exile. As a result, a literary bridge was built between them and Kurds all over the world. Their works were transcribed from the Cyrillian to the Latin alphabet, through which their literary production reached out to Kurdish readers and intellectuals in various parts of Kurdistan.

1932 – 1943: The Hawar Era

Celadet Badir-Khan, grandchild of the Prince of Bhutan, Prince Badir-Khan, and son of the well-known Kurdish intellectual Emin Ali Badir-Khan, left München for Istanbul in 1920 to study for a doctoral degree. The Republic of Turkey, founded in 1923, made it impossible for him to return to Turkey. He therefore moved to Cairo where he lived for some time, before moving on to Damascus. Several other successful intellectual Kurds were also forced to leave Turkey for Damascus. Celadit Badir-Khan, author and lover of literature, regards life in exile as a factor that enhanced his writing and his life in general. The Kurdish people’s predicament—Kurds coming from many different parts of the country—moved him, so in exile he continued his work on a Kurdish grammar, work that he had already begun. Aided by the Kurdish community in Damascus and the vast knowledge and experience he had amassed over the years he lay the foundation of the Kurdish grammar. They also created the Kurdish alphabet and begun translating poetry, short stories, novels and drama from world literature. Moreover, supported by the recently constructed grammar, he published the magazine Hawar, which in turn became the foundation of modern Kurdish literature. Most writers who contributed to Hawar were Kurds in exile from various parts of Kurdistan.

In other words, the seeds of modern Kurdish literature were sown in exile and have continued to grow in exile. Within ten to fifteen years Celadet and Karan Badir-Khan between them published five magazines. Alongside Hawar, they also established the Hawar Publishing House that published books in Kurdish in all kinds of genres. Most of these books were written or translated by the brothers Celadet and Kamran Badir-Khan. The Kurdish language that grew out of this activity was characterised by a classic style and Kurdish folklore. Hawar became a bridge between classic and modern Kurdish literature and between Kurdish and international literature. Alas, after ten years of publication Hawar experienced an economic crisis that contributed to the early death of its owner Celadet Badir-Khan and thus ended one of the most flourishing periods in the history of Kurdish literature.

The Coup, the Vulnerability of the Kurds, and Living in Exile in the 80s

After the fall of Hawar there followed a silence as concerns Kurdish literature and the Kurds became more and more distanced from their language and their identity. In the period between the 1920s and the 1980s only four or five books were published in Kurdish in Turkey. This was the situation when the junta took over after the coup d’état in 1980. Under the rule of the junta, thousands of Kurds were arrested and equal numbers fled the country. The young men and women who fled after the coup were spread out over the European countries and many of them came to Sweden. However, even before 1980, such pillars of Kurdish literature as Cegerxwîn, M. Emîn Bozarslam, Mahmut Baksi, and Mehmed Uzun were already living in exile in Sweden. In Stockholm in 1981 the Federation of Kurdistan Associations was formed and thereby Kurdish organizations from all over Sweden came under one umbrella. Following its establishment this federation published a magazine called Berbang. Since it was published in Kurdish the magazine played a salient role in developing the Kurdish language and its literature. After Berbang and Nûdem, dozens more Kurdish magazines popped up in Sweden and some ten publishing houses were instituted that published in Kurdish. However, the magazines and the publishing businesses have become fewer, and now, for the first time, they have begun to move back to Turkey.

The 90s and Publications in Kurdish in Istanbul and Diyarbakir

After the 90s, and especially now in the new millennium, there is a noticeable development of the Kurdish language and its literature in Istanbul and Diyarbakir. Kurdish magazines and newspapers are being published, new publishing houses are being established, new books are being printed. This is the first time after the foundation of the Republic that Kurdish is used with such intensity in publications and media. Today there are many Kurdish publishers who have published thousands of titles in Kurdish in Turkey. Despite marketing challenges, despite Kurdish not being a language of learning in the schools, and despite the suppression of the Kurdish press, the Kurds unremittingly continue their work to forward the Kurdish language.