Words Widen our World

When the Arab Spring started in Tunisia in 2011 and rapidly spread to the rest of the Arab world many of us saw this as yet another sign that democracy was conquering the world.

We were used to this idea. We recognized the pattern.

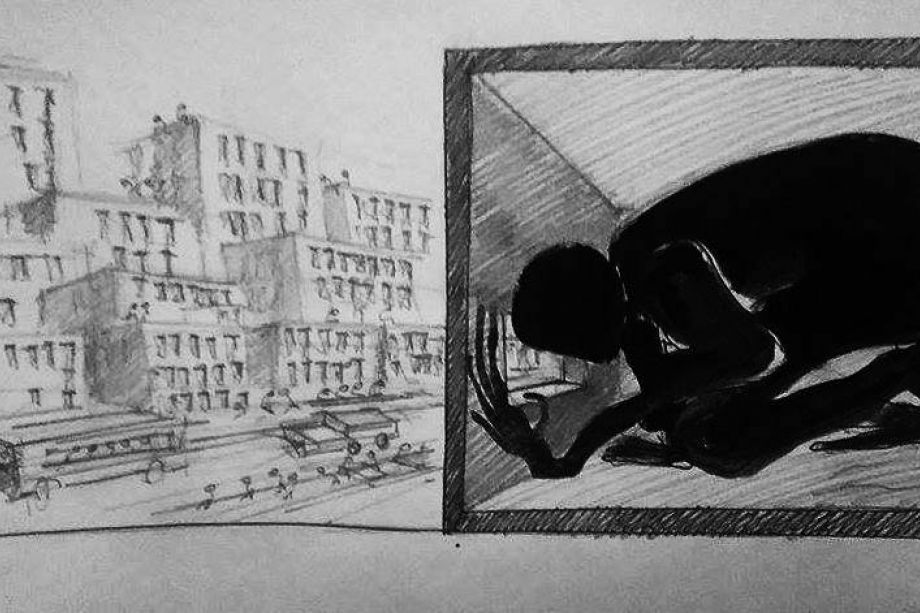

Heavy authoritarian states may seem impenetrable as if they could remain intact for ever, but under the surface there is always an on-going movement among the people; there are processes underway, meetings, talks, and debates that will eventually overthrow any dictatorship or oppressive system.

We saw it in the former Soviet Union and in Eastern Europe in 1989. We saw it in Latin America during the 90s and we thought it was happening in the Arab world around the turn of the century.

Today we know that the development towards democracy does not follow a set course. In one country after another in the Arab world, in the aftermath of the peaceful revolutions, which for a while seemed to open up for democracy in these regions, repression has returned.

And in the past few years the same tendency of repression has escalated in several other countries such as in Cambodia, Hungary, Poland, and Russia; the freedom of speech cannot be taken for granted. Those in power are shortening the leash, forcing journalists, writers, and other intellectuals to adhere to the political norms that the regimes dictate. Those who refuse, those who still insist that free and critical thought and speech have a right to exist, are harassed, imprisoned, forced into exile, or even killed.

Repression in the Arab world is thus just one more example of this tendency.

Of course, one should also remember to differentiate between the various countries; in some countries mentioned there still exists a degree of freedom. In Tunisia, for example, the Arab Spring has not been suppressed. Here the euphoria of the revolutionary months has been transformed into parliamentary and civilian action to build a stable democracy—not without difficulty but still not under threat. In several other countries journalists, writers, and other intellectuals, who briefly more openly could write, speak, and express themselves, have needed to go underground.

In other countries the boundaries are less clear. Here there may be leeway for free expression, but there are also definite no-go zones of a political, ethnic, or religious nature, and many who are still active in these countries need to be extremely cautious.

In this issue of PEN/Opp we have assembled texts written by a few of these intellectuals. Our guest editor, Trifa Shakely, has had the ambition to find voices that are rarely heard. It is mainly about modern contemporary writers who use a new way of writing. An easier language, instead of the classic Arabic. These voices cannot possibly reflect the whole of the Arab world, but they can give us some insight into contemporary reality, give us fantastic images of everyday events and of small steps of development in the writers’ countries, impart images of life in exile, of on-going resistance, and continuing oppression.

In combination these images come to symbolize something vital: they show that the right to free expression can make life better and more fun to live and it can open up the world to the experiences of others.

Jesper Bengtsson

President, Swedish PEN