'Dogs Are Not to Blame.'

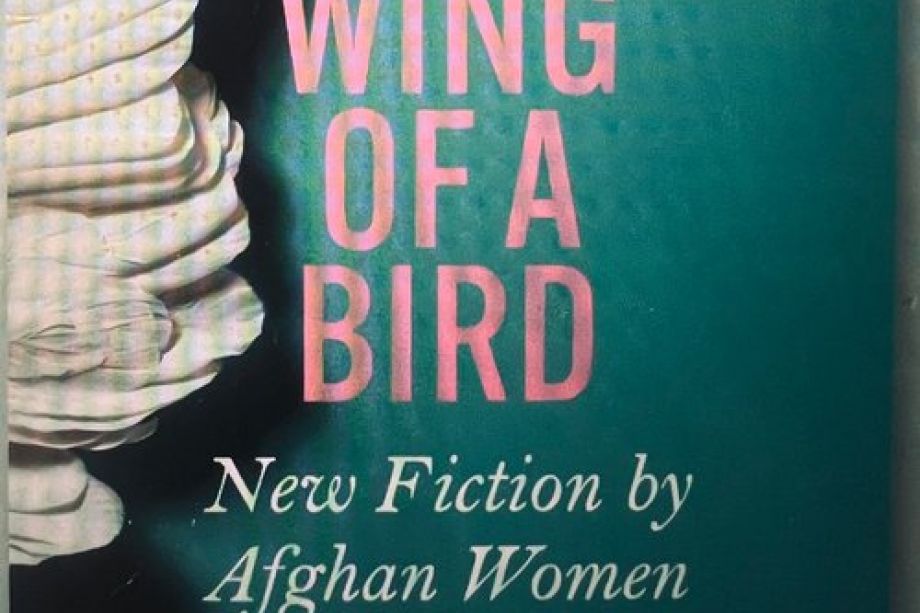

In modern Afghanistan years of instability and internal displacement have created a challenging environment for writers of all kinds. The majority of Afghanistan’s writers that have been given international attention through English translations are men; most of them living outside of the country. The same is true of the small number of Afghan women who make their living through writing. In a nationwide bid last year the Untold - Write Afghanistan programme (www.untold-stories.org) asked Afghan women to submit short texts in fiction. Masouma's story was chosen from the 120 submissons and she joined the Untold - Write Afghanistan programme. She is one of 18 writers from this programme to be published in the anthology, My Pen is the Wing of a Bird: New Fiction of Afghan Women (published by MacLehose Press/Quercus 2022).

In dialogue with the founder of Untold, Lucy Hannah, PEN/Opp has been given permission to publish the short story, “Don’t Blame the Dogs" by Masouma Kawsari.

Kawsari was chosen by a team of Afghan readers for her distinct voice and the power of her storytelling which can be of interest for both local and global readers. Masouma Kawsari will continue to work with Untold’s editorial programme, from Sweden where she now resides, since the Taliban retook Kabul in 2021.

It looked worse when Saber was sitting down. His shadow on the wall seemed particularly lumpy. With his body curved over the paper, a person would think he was searching for something between the lines. He was thin and tall, but sitting like that made him look small, the curvature of his spine visible.

Saber was a petition writer. Getting this job had not been easy. He had no savings to open a garage. Carpenters were not doing well, and he couldn’t afford to buy a sewing machine to work as a tailor. He had no connections, either, and didn’t know anyone in the government offices. In the end, he concluded that there was no work for him anywhere in the city.

He had been very young when his father abandoned him and his mother. She had worked in people’s houses when he was growingup. Now, in her old age, she was still doing the same job.

After years of searching for employment, Saber was able to rent a spot from the municipality on Sarak-e Mahkamah – the footpath that led to the courthouse. Some petition writers had their own sunshade; others, like Saber, sat under the can- opies of the shops that lined the path. A thin, weak-looking man approached and stood in front of Saber’s desk.

“Do you write petitions?” the man asked.

Saber had wrapped his shawl tightly around him to protect himself from the wind and rain. Only his hands in their fingerless knitted gloves were visible.

Without looking up, he said, “Hello. Sure.” He pulled out a form from the drawer of the small, old metal desk he worked at. The paper fluttered in the strong wind.

“Have you brought your tazkera, a passport photo and photocopies of your documents?”

The man reached quickly into his jacket pocket and pulled out a plastic bag. He placed it on the desk.

Numb from the biting cold, Saber’s fingers could hardly close around the pen. “Give me your tazkera,” he said. The man hurriedly pulled the papers out of the plastic bag and handed Saber his ID card.

Resting a small stone on the papers to protect them from the wind, Saber nodded at the plastic chair in front of his desk.

The man sat down, looked around him, then turned his head and spat out the quid of tobacco he’d placed under his tongue. He wiped his mouth with the end of his sleeve and put his prayer beads in his pocket.

“Your name is Nazir?”

“Yes, it is.”

“Son of Shir Khan?”

“Yes, sir! I have a fruit and vegetable stall in the market.”

Nazir pushed his head close to Saber’s and dropped his voice to a whisper. “My father had two wives. When he died, my half-brothers did not give me my share of the inheritance.” Saber’s pen was not working. He scribbled on the paper a few times, but it still wouldn’t write. He secretly swore at the manufacturer of the pen, borrowed one from the petition writer next to him, and started filling in the form.

“Name. . .Nazir,son of ShirKhan. . .Permanent address. . . Current address . . .”

The man turned his head again and spat on the snow, the green of his saliva lighter than before.

“They said to me, ‘You are not a son of our father and he did not mention your name or your mother’s in his will.’ I am now making an application for my rights as well as for my mother’s. My father did not support us while he was alive. My mother worked in people’s houses. We wore second-hand clothes and ate people’s leftover food all our lives. I didn’t go to school because we couldn’t afford it. He didn’t marry me to anyone.”

“Why didn’t you lodge an application to secure your rights and your mother’s rights when your father was alive?” Saber said.

“Sir, I am illiterate, and my mother does not understand these things. Whenever I talked about it, she would say she had to protect her honour. She says people should not be given reason to gossip about my father. They would say she was badly raised because she did not stand by her husband and failed to endure the difficulties of married life.”

“Do you have a witness if one is needed later?” Saber said. Nazir got up from his seat. He adjusted his shalwar, wrapped his shawl around him and pushed his hand into his jacket pocket. He pulled out a small plastic bag of tobacco, took a pinch and placed it under his tongue. Shoving the bag back into his pocket, he retrieved his prayer beads and recited a quick prayer.

“Yes, sir! I have many witnesses.” The quid in his mouth muffled the man’s voice. “All the people in the area are my witnesses. They all know me. I can bring as many as necessary.”

Saber completed the form. After haggling over the fee, Nazir took the document and left.

Nazir was Saber’s first customer and it was already noon. The icy wind that swept up the streets and shook the awnings of the little shops hadn’t let up. The pungent smell of the nearby toilets wafted into his face.

From the mosque on the road behind the court, the call to prayer cut through the air. Some petition writers pulled plastic sheets over their desks and hurried off to pray. Saber had long ceased to go to the mosque or pray. He had become uncertain of everything – even of God. He pulled a plastic cover over his desk, looked up at the grey sky, and went to the high concrete wall they’d built around the court a year ago, after a suicide bomb attack. The municipality had painted pictures of the old part of Kabul on it. One image was of Darul Aman Palace, which was rebuilt after the war. Another was of a girl giving a flower to an Afghan soldier. At the bottom of the wall were urine stains, some of them still wet.

Saber covered his nose and mouth and wrapped himself in his shawl. He untied the string of his shalwar and relieved himself, the drops of urine falling onto his shoes and the hem of his shalwar. The rising steam hit him in the face. He straightened up and watched the yellow liquid flow from the bottom of the wall towards the sewer that ran along the road, mixing with the melting snow and rain.

Saber retied the string, then bought a bolani from a nearby cart. He returned to his old metal desk, took the stuffed flat- bread from under his shawl and bit into it. Bits of leek caught between his teeth. He removed a thread from his shawl and flossed his teeth with it, swallowing the fragments of food it dislodged.

He was about to finish the food when he noticed the dog. The bitch was lying with her puppies in the hole leading to one of the toilets.

Her pups were sucking on her teats. Her eyes were on him. Saber got up, threw the last bit of bolani to the animal, rubbed his greasy hands together, then wiped his mouth with a corner of his shawl before sitting down again. He had noticed the bitch during the early days of his work at the courthouse. She would often sleep opposite him, and other petition writers would sometimes throw her a piece of bread too. The dog had disappeared for a while. When she returned, Saber realised that she was pregnant. Now that her pups were born, he would focus on the animal whenever he had no customers, or had nothing to do.

He took his quid tin out of his shirt pocket and knocked it against his palm several times. He looked at the right and left sides of his face in the small mirror attached to the back. His face looked thinner and paler than usual, his eyes sunken. Saber ran his fingers through his sparse beard. The hat his mother had woven for him completely hid his hair. His nose, now red from the cold, resembled an eagle’s beak. He opened his mouth and examined his teeth, took a small portion of quid from the tin, and placed it under his tongue. The tobacco tasted bitter, but it was that bitterness he liked. It made him feel better.

Saber poured himself a cup of tea – the last left in his flask. The rising steam gave him a pleasurable feeling of warmth. It had got colder but it was no longer raining or snowing. He wrapped himself more tightly in his shawl and spat out the quid. The particles fell on the snow and immediately froze.A passer-by stepped on them and they disappeared under his feet.

A woman in a blue burqa came and stood by Saber’s desk. She looked along the footpath, her gaze pausing on each of the petition writers.

“Can I help you, Maader?” Saber asked.

“Salaam,” she said.

Saber nodded in response. It was clear from the wrinkles around her eyes, which Saber could see through the netting of her burqa, that she was an older woman.

“I want you to write a petition for me. I have heard that yours are better than the others’.”

Saber smiled and gestured at the chair. She sat on it, her plastic shoes buried in the slush, and immediately began to talk. She sounded tired. It was obvious that she’d had a hard life. Her hands reminded Saber of his mother’s, whose skin had become so thin from doing people’s laundry that she needed to apply Vaseline to them every night.

The woman adjusted herself on the chair. “I was very young when I got married. My husband was killed in the conflict, leaving me alone with my six children. My elder brother-in-law, who has a wife and children, said to me, ‘You will either marry me or I will take my brother’s children from you.’ I had to marry him for the sake of my children. His first wife did not allow him to support us. I worked and raised my children myself. My brother-in-law had a fight with a man over land. He killed that man. Now he wants to marry my daughter to his victim's brother as repayment." The woman sniffed then wiped her tears with a corner of her burqa.

“Should I write the petition on your behalf or on your daughter’s?” Saber asked.

“No, no! On my behalf. If there is any problem in the future, I will deal with it. My daughter can’t.”

“Do you have power of attorney for your children?”

“No, what is that?”

“You should have secured it while their father was alive. To my knowledge, power of attorney goes to the paternal uncle or grandfather.”

“I don’t understand these things. All I know is that they are marrying off my daughter by force.”

“The petition should reflect your daughter’s own words,” Saber explained. “Do you have any documents?”

The woman sniffed once more and pulled out some papers from a bag. At the top of the bag, which bore a picture of rice, she had sewn a large metal zip to make it more secure. From among the documents, she took out her ID card, her late husband’s and her daughter’s, along with a handful of photos that she placed on the desk.

Saber inspected the IDs one by one, then looked at the photos. “These photos are from a few years ago. You must take new ones.” The woman looked helpless. She picked up the photos and stared at them. “Can’t you use these? It is difficult to get my daughter out of the house. They do not allow her to go out.

That is why she had to quit school. If they find out, I will be in trouble.”

“No, it is not possible; these photos are of your daughter when she was a child.”

The woman said nothing for a few minutes. Finally, she returned the documents to the bag.

“Take the photos and come back,” Saber told her gently. “Then your job will be done. I will find you witnesses here. Just take some new photos of your daughter and yourself.”

The woman stood up and walked away. Saber watched her disappear at the end of the road, her footprints quickly erased by the snow, which was now falling heavily.

Some petition writers had called it a day and left. The photog- raphy shop at the entrance of the street had closed earlier. On cold afternoons like these, the courthouse street was often empty and silence would prevail.

The puppies had drunk their fill. Now they were climbing over the bitch’s neck and head. They would sometimes come to the opening of the hole and then retreat. The mother was lying casually on the dirt, looking out. A strong wind blew the pungent smell of the toilet, along with the odours of the sidewalk, into Saber’s face. He was used to these smells; he was not bothered by them.

A group of girls from the training centre on the adjacent street passed by Saber’s table. One of them bent down, picked up a handful of snow and threw it at the girl ahead of her. The sound of their laughter cut through the silence.

It reminded Saber of a girl he had once seen in the training centre when he was a student. He had spotted her only a few times and, because he was shy, he had not dared get any closer to her.

She was different from other girls and looked prettier when she laughed. Saber had taken a photo of her without her realising.

He had seen her entire family – almost! Sometimes he would follow her to her house, though always from a distance. He would walk or borrow his neighbour’s son’s bicycle to ride to her street. Once there, he would imagine the girl’s photo on all the walls of the houses.

Then he found out that she had a fiancé abroad, and would one day travel to be with him forever.

“You’re biting off more than you can chew, Saber,” his mother had told him, but his heart was not ready for such talk.

Eventually he accepted his circumstances: that he was unemployed, had no home of his own, and that his mother worked in other people’s houses. But he could not forget the girl, Meena.

The street was now deserted except for Saber and a few others spread out along the footpath. Saber lit a spliff and settled down to smoke. He put the spliff between his lips and took a deep draw. This was the only thing he really loved – his only real comfort. The smoke wafted through the air, multi- plying Saber’s pleasure. It no longer mattered to him that his father had abandoned him.

He was not ashamed that his mother did the laundry in the neighbours’ houses and that she would bring home their discarded clothes. He wished happiness for the girl he’d loved for a few days and admitted that he could not have made her happy. Now he longed for someone with whom he could talk – to tell them who Saber was, what he liked, what he wanted to do, where he wanted to go, and what he was capable of.

He was lost in these thoughts when the petition writer next to him shouted, “Saber, do you plan to stay here all night?” He quickly came to his senses. “No, Kaka. I am leaving.”

He got up and hurried towards the pavement. Almost everyone was gone, and the court staff were getting into shuttle buses at the courthouse gate. Saber cleared his desk. He had already put his cup and other things in the drawer. He locked it, and then, like all the other petitioners, he took his two chairs back to the market to rent out.

The snow was falling even more heavily when Saber returned to the courthouse footpath. He sat near the toilet hole and looked at the puppies. They were still little. He thought that they might die of cold and hunger overnight. He could not take them home – they did not have space and his mother would be angry. Nor did he have the money to get bread for them. He had earned just enough to buy food for that day, and to cover the next day’s expenses.

He approached the bitch and gently petted her. The warmth of the dog’s body was pleasant under his hands. She was breathing slowly, her ribcage moving up and down.

Saber drew closer. How lonely was this dog? How did she manage with her puppies in this cold weather without food? What if they froze to death by the next morning? The dog must have felt his love because it remained calm under his touch.

He had never experienced love. His mother neglected him, especially if she was tired after work, or upset because of the landlord’s behaviour. She blamed him for all their troubles. “If you had not been born, I would have remarried. Your cowardly father didn’t do me any good.”

Saber’s teachers had shown him no love either. They pitied him because they knew he was poor and had no father. His classmates bullied him and called him Saber-e Kopak – Saber the Hunchback.

It was getting dark. A few houses had their lights on. Tonight, it was their turn to have electricity.

He thought of his mother. She would be home by now, waiting.

A cold wind was blowing along the street. Saber felt even happier. He imagined Meena, the girl he loved, smiling, dimples forming on both cheeks. Her hair – glimpsed from under her headscarf – was long and braided. Saber reached out to touch it. It was soft and delicate, like silk, and smelled sweet. He moved his lips closer to kiss it, but pulled back when he noticed that the bitch was following one of the puppies into the toilet hole. Embarrassed by his fantasies, he smiled.

Saber got up with difficulty and shook the snow off his clothes. He lowered his hat over his head, tightened his shawl around his body and left for home. Silence, darkness and the cold surrounded him.

Occasionally, the sound of a car playing loud music could be heard from a distance, then it would pass by at speed.