The easiest way to escape from prison: literature

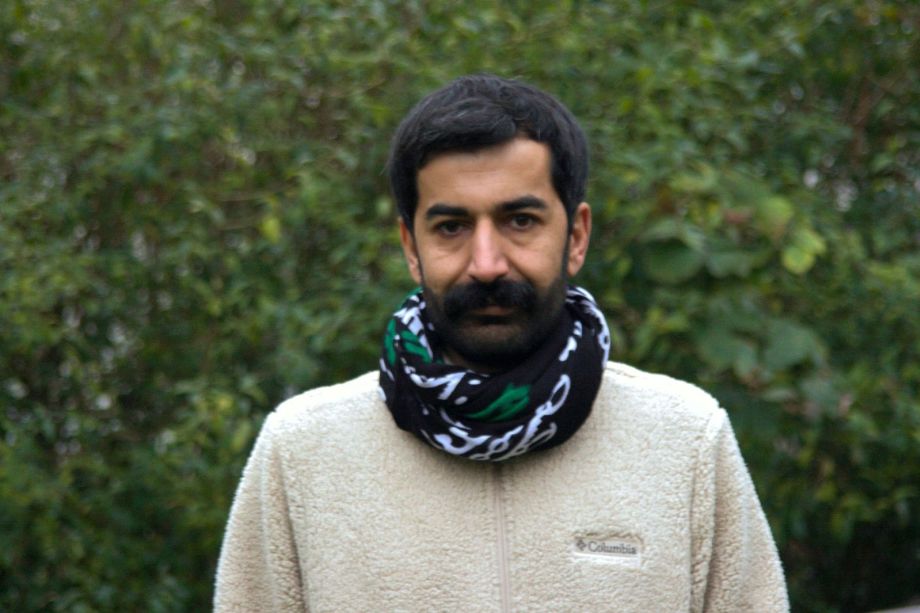

Kurdish poet and journalist Nedim Türfent spent more than six years in Turkish prison for his journalistic work. For PEN/Opp, he describes life behind bars and how letters and literature kept him alive.

I am a citizen of a country where a pen is considered to be more dangerous than a gun, a book more hazardous than a bomb. I am not saying this just for the sake of argument. In a speech in 2011, the Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said, “There are such books that are more dangerous than bombs.” He defended this ‘unique’ view several times. If the leader of a country holds an ‘opinion’ like this, no wonder that writers, poets and journalists living in that country are subjected to repression. Believe me, it is impossible to describe all the oppressions in a single article! I have myself experienced my share of the oppression of this dystopian regime, as have hundreds of other colleagues who have held a pen in their hands.

Turkey ranks 158th out of 180 countries in the 2024 World Press Freedom Index of Reporters sans frontières. Hundreds of writers, poets and journalists have been arrested at different times and have received long-term prison sentences in Turkey, especially in the last 10 years. The award-winning Kurdish poet İlhan Sami Çomak, an honorary member of several PEN centres, was released on the 26th of November after 30 years and 3 months in prison.

Dozens of journalists, writers and poets are still behind bars in Turkey. Turkey has become a prison for journalists and writers. Furthermore, Erdoğan’s one-man regime imposes new restrictions on freedom of expression and thought every other day. In Diyarbakır, the largest Kurdish city in the country, the Turkish prosecutor’s office issued a recall order against 47 books, 12 magazines and 6 newspaper editions. This decision is not something from the past; it was made on the 12th of December 2024. In other words, in the 21st century!

According to the latest report of the Dicle Fırat Journalists’ Association, a non-governmental organisation that regularly monitors violations against journalists, in Turkey, since the start of 2025, 40 journalists have been detained and 15 journalists have been arrested. Currently, 37 journalists are in prison for their journalistic work. And in the last six months, six Kurdish journalists were killed in Turkish drone attacks on the Federal Kurdistan Region of Iraq and the autonomous Rojava region in Syria.

I was carrying a few pens, two notebooks, my computer and my camera. According to the Turkish government, this journalistic equipment constitutes an element of ‘crime’!

As a journalist working on human rights, I was detained on the 12th of May 2016. I was carrying a few pens, two notebooks, my computer and my camera. According to the Turkish government, this journalistic equipment constitutes an element of ‘crime’! One day later, I was arrested for “being a member of an armed terrorist organisation”.

Many international organisations that work in the field of freedom of expression and journalism started to campaign for me when they learned about my arrest. PEN International launched their first solidarity campaign for me in December 2018. A year later, hundreds of fellow members from 25 PEN centers signed a global call for my release and my story was featured on the Day of Imprisoned Writers and World Poetry Day. My poem “Let your heart give life” was translated into 20 languages. In 2020, an advocacy campaign was organised to commemorate the 1,500 days I spent behind thick walls, and in 2021 another call was made on the occasion of the 2,000th day of my imprisonment. On the 29th of November 2022, after 6 years and 7 months of imprisonment, I was released.

What happened inside the walls of the prison while these campaigns were being organised outside? Do the support and solidarity campaigns have an impact or result? As far as I know, campaign organisers, and those who support these campaigns, can sometimes be quite pessimistic about the effects of this kind of support. I will return to this in a moment and what it can mean for someone to be the subject of the campaigns.

I have spent twelve years as a journalist. Throughout my career, more than half of which I had to spend in prison, I never put down my pen or my camera despite receiving death threats from the Turkish police. When I was detained, they confiscated all my journalistic equipment. When they arrested me, they gave me back my pens and notebooks but not my camera.

I longed for my camera but held my pen tightly since it allowed me to continue to express myself. I started to write about the rights violations experienced by political prisoners and about the stories of other imprisoned journalists. I sent my articles to newspapers both in Turkey and abroad by letter and through my lawyer. The prison administrators and the Ministry of Justice were so disturbed by my reports that they placed me in solitary confinement. They put me in a solitary cell to prevent me from contacting other people and writing articles and case histories. The prison administrators even imposed a book embargo at the beginning of my isolation. This period coincided with the campaign of international organisations.

Now I will return to the effect of international campaigns. After the letter campaigns “PEN Writes” and “Letter with Wings”, I received messages of solidarity from more than 30 countries. As the campaign grew, my prison conditions started to improve. When the prison administrators wanted to violate one of my rights, they had to think twice. They took me out of solitary confinement due to their concern that international support would grow even more.

While support and solidarity campaigns can sometimes bring freedom sooner, they also have other effects and consequences. Campaigns can help to improve prison conditions and thus can allow you to breathe within those four walls. And what is even more important is the moral and psychological strength that campaigns and letters provide you. Every word in each letter that reaches your hands, overturning walls and borders, instils strength in your veins and hope in your soul. Your belief in the power of the pen and words is further strengthened.

After receiving letters from all over the world, from Mexico City to Dublin, from Toronto to Stockholm, I began to see my pen as a limb of my body, so to speak. I knew that I could no longer live without it. In the solitary cell where I was put so that I would not write news articles and case histories, I began to compose poetry. The poems I wrote from that narrow cell where I was kept alone for 18 months were translated into different languages around the world.

The main purpose of authoritarian regimes in confining a writer, poet or journalist within a prison is to prevent his or her voice from being heard. When this suppressed voice is then heard in different languages all over the world, it is a great blow to the enemies of freedom of expression.

A friend from PEN sent me translations of my poem “Let your heart give life” in 20 different languages. In the prison where I was held, letters were distributed on Wednesday and Friday every week. The term ‘letter day’ is even used for these two days. For the prisoners, letter day has a special meaning, and a unique excitement arises in their hearts on that day. The correspondence guardian, who checks and distributes letters, goes from ward to ward, opening the small grille of the cell door and delivering the letters. When the guardian handed me a large envelope, he said: “Nedim, this big envelope contains translations of one of your poems in many languages. We don’t know which language some of them are. But since it was a translation of your poem, we didn’t investigate them. They supposedly locked you up here to silence your voice. But that voice is much louder now.”

By the way, the correspondence guardian has to read, scan and record every letter, no matter who the sender or recipient is. It is his/her job to read other people’s letters! In other words, he/she reads another person’s private correspondence and is paid a salary by the state for it. It sounds quite ridiculous, and it is of course absolute nonsense.

When I was released after almost seven years of imprisonment, I came out of prison with a mountain of letters. I am exaggerating, of course, but I took boxes of letters out of jail with me. Letters were one of the most fundamental things that kept me alive during all my years of captivity. Another one is books, from stories to novels, from poems to research. When you are locked in the dark box of prison, your contact with people and real life is minimal. Wherever you look in this cramped space, you encounter walls. Day and night, you look at the walls and manage to overcome them. You achieve this with your vast horizon, which turns the wire fences upside down, and your imagination breaks down the thick grey iron walls.

So, is there a factor that causes your imagination to enrich and become endless? There certainly is, and it is none other than literature. Literature offers a space for people who have been locked up to find and express themselves. Literature makes it possible for people who are isolated to socialise. Literature is one of the rare ways for people to recover from the trauma of imprisonment. This therapeutic effect of literature is vital for both the soul and the psyche of the imprisoned person. Moreover, the body of a person, who feels spiritually alive thanks to literature, becomes more resistant to the poisonous and dulling conditions of prison.

In fact, it is your salvation if you place yourself in the therapeutic arms of literature in the prison in which you are locked up. As a matter of fact, when a person reads a story or a novel, he/she also embarks on a journey with its protagonist. In this respect, literature is the easiest, fastest and most accessible way to escape prison.

The moment you take the pen in your hand, and start swimming in the world of words, you are free.

After going on these journeys, if I may exaggerate a little, as many times as there are stars in the sky, words accumulate inside you like a huge sea. It’s a blue sea of colourful words. On the other hand, since you are being kept away from human contact, you are searching for an opportunity to express your words. The destination of this long-standing search is the act of writing. People whose speech is restricted in prison resort to literature so that they can express their words. In my opinion, the fact that people who are locked up in prisons for a long time turn into writers or poets after a while is the most naked and clear evidence of this. Once you take the pen in your hand, no walls, wire fences, iron bars, handcuffs or shackles can imprison you anymore. The moment you take the pen in your hand, and start swimming in the world of words, you are free. In short, literature liberates.