An Observation on the Role of the War Impacting Contemporary Afghan Literature:

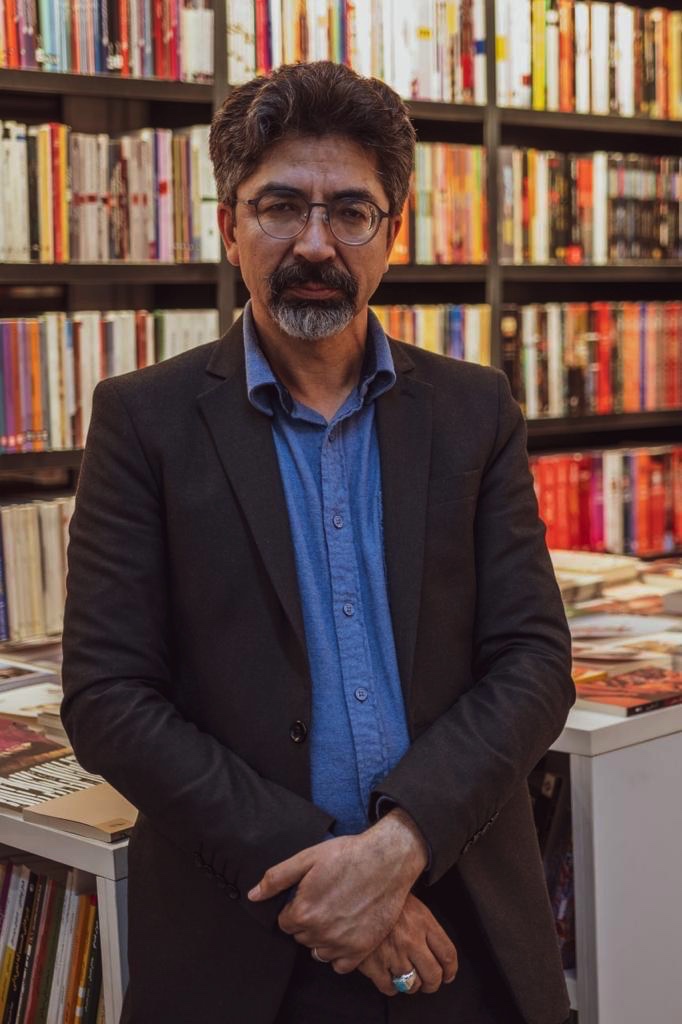

Zia Qasemi, born 1975 in Behsud, is an Afghan poet, author and also guest editor for this issue. He has published two novels and three collections of poems in Iran and Afghanistan and has won several literary awards. In this article, he examines how the voice of protest is shaped in contemporary Afghan poetry.

Qasemi lives in Sweden.

From Heroes and Anti-Heroes to Murderers and Slayers

Without a painful and burning weeping, buried in blood,

the lover of the friend has died, Majnun is asleep.

Walk gently next to her,

Kabul with a thousand wounds drenched in blood.

This quatrain is by Afghan poet Abdul Qahar Asi, and it is an accurate reflection of the literature of Afghanistan over the past decades. It also reflects the lives of Afghan people and poets immersing in the bloody war and its aftermath. He was a poet, who like many more of his Afghan fellows, became a victim to Afghanistan’s long-running wars. Since the morning of April 27 in 1978, when the people of Kabul woke up to the crowding sound of tanks and guns by the coup plotters of the People’s Party and at the start of the war, there have been very few literary works produced in Afghanistan without traces of war and violence in their making.

In the early years of this war, two sides confronted each other ideologically, and literature received its effects. Literature was once considered a work of the prophecy, now it bore the burden of motivation and encouragement of its like-minded people to fight and struggle. On the one hand, some poets and writers leaned toward leftist ideas, alongside the government of the time writing about issues on social justice, the establishment of a classless society, and fighting for the rights of workers and peasants. They invited the reader to fight against reaction and arrogance. On the other hand, writers with religious tendencies and sympathy for the Mujaheddin groups encouraged their readers to fight against the state to defend religion and homeland and preached for a Jihad—holy fight against infidelity and occupation.

In the literature produced by these groups, war was never inherently condemnable. Devastation, death, and other damaging effects of the war were only presented by the opposing group, but their self-images in connection to the homeland reflected bravery, courage, and sacrifice as if every bullet fired and every wound inflicted was sacred and valuable.

We are the rightful Mujaheddin, the grace of God is with us,

wherever we go, the hand of the Almighty is with us.

From the extent of the trenches, the eye of Prophet is on us,

at dawn, the good news belongs with us.

In the figure of the nation, we are their competent arm,

we are the trust of today and the pride of tomorrow.

With my loud voice of Takbir, the back of the enemy trembles,

the enemy shivers in the bone marrow fearing me.

With the glory of my sword, the heart of traitor trembles,

the sky at last shivers down due to my nocturnal prayers.

The throne plays me a song, the threshold sings me a song,

in my melodious chant of “La ilaha illa Allah” [there is no god except Allah].

(Khalilullah Khalili, Poetry Divan, p. 421)

It has been years since the burning sun of

Saying Takbir is bright.

For how long you the people be willing to wash off

the chains of torture with tears?

For how long will this crying from the graves

of the prisoners be heard?

My ear is thirsty to hear the roaring sound of the chain.

With the lightened torch of Lenin's thought,

With a stormy, heated and bloody uprising

Break these chains and bridles—

Break this bondage,

to face the bright future and face

the eternal freedom.

(Assad Ullah Habib, Farewell to Darkness, p. 11)

These contrasting views always have had almost a common spirit. Only the symbolism and their poetry were different, otherwise, each of them introduced himself as a patriot and the other as the enemy of the homeland and the agent of foreigners. Apart from the differences in form and structure, both groups have common themes in their content and meaning, and only that they refine the hero and anti-hero to possess their images. It should be noted, that to look for good quality, the literary works of these two groups, either in poetry or fiction, were never comparable.

Today, Afghan society has dissociated itself from those thrills. But if we are to understand them impartially, we find that the literature of the left-leaning was more powerful, both in poetry and narrative form, due to its centralized activity, use of government facilities, connection with the world of socialist literature and more reference to new structures, and there was a kind of richness in the themes. More precisely, in fiction, the Mujaheddin had no other works other than one or two discreetly neglected novels, such as Dragon Crowd by Hatem Amiri and My Russian Friend by Isaaq Fayyaz, and a few short stories. However, the leftist novelists were more active, and they published several notable works during that period. Works such as the two novels, Sickles and Hands by Assad Ullah Habib and The Red Road by Babrak Arghand.

But as the direction of the wars in Afghanistan changed, the literary community's approach to war also transformed. The changing tone brought in the quatrain at the start of this article is a mirror of that whole picture, refining it as the anti-war literature.

The intense internal divisions of the ruling left, which at times escalated into bloody purging, followed by the rise of the Mujaheddin government and the undeniably fierce power struggles between Mujaheddin parties, and the subsequent domination of the Taliban, all condemned the war in the eyes of all people, including writers. The catastrophes and devastations of war were so great that they could no longer be sanctified with the garment of any ideology or act of purification.

And it was then that Afghan literature, especially with the emergence of a new generation of poets and writers inside Afghanistan and those Afghan immigrants abroad, took on an anti-war approach. Such examples are, Atiq Rahimi’s novel Earth and Ashes, the short stories such as Tazkereh by Spôjmaï Zariâb, The Groom of Kabul by Mohammad Asef Soltanzadeh, and The Deaths by Mohammad Hossein Mohammadi; these were among the first of this trend of fiction writing by Afghans. This was a period in which there were no “heroes” and “anti-heroes”, but the story was the story of “murderers” and “victims”, and a similar atmosphere was traceable in poetry. The story was about the soldiers, who were killed so that the commanders behind the negotiating peace tables could make their points. From then until today, the stories and poems of Afghan writers are full of images of explosions and wounds and destruction. This is a story to narrate the periods in the history of Afghans for tomorrow and the future.

May God bless the grapes to ripen,

so, the world gets drunk,

and the streets feel like the rolling motion,

and fall flat on each other’s shoulder,

presidents and beggars

and the borders get drunk

So, Mohammad Ali could meet his mother after seventeen years,

so, Amina could caress her child after seventeen years,

May God bless the grapes to ripen,

so, the Amu River brings up her most beautiful sons,

so, the Hindu Kush Mountain frees his daughters,

for a moment,

so, they can forget their guns,

for rending,

so, they forget the knives,

to cut open,

so, the pens start a fire

and write down a ceasefire.

(Elias Alavi / Hudood, p. 7)