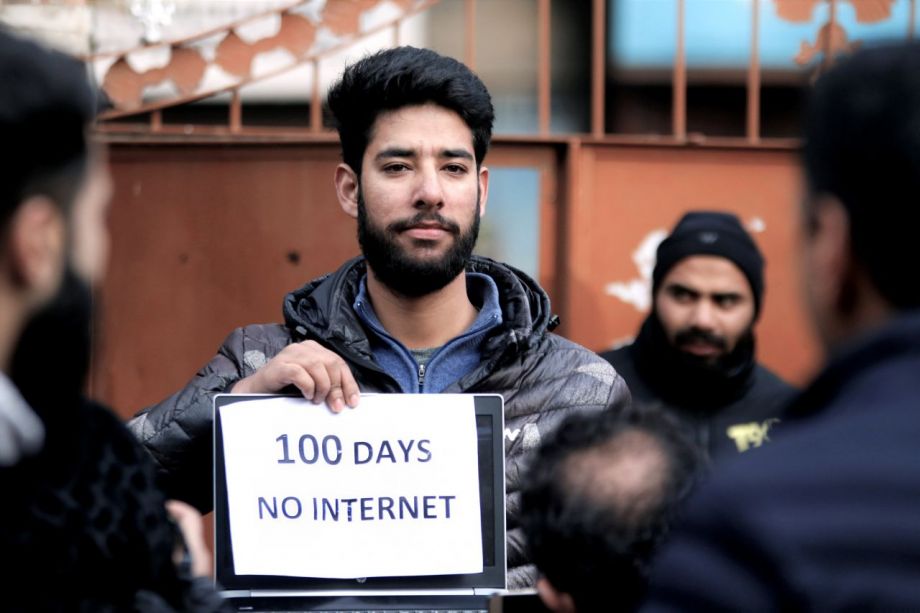

164 days without the Internet

In troubled Kashmir the Internet has recently been shut down for 164 days. This has been the longest ever shut down of the Internet in a democratic country. On January 25 the government restored the Internet—albeit under highly restricted forms. In a personal text the journalist Aakash Hassan describes what the shut down has meant to people, and journalists in particular, by way of practical difficulties. “When my grandmother passed away I was on a reporting assignment, and, although I was only a one-hour drive away, it was impossible for my family to in time convey to me the sad news,” he writes.

On August 4 in 2019, midnight Kashmir vanished from the virtual world map when the internet, all mobile phones and the fixed landline network were shut down in a snap.

Young lovers in the middle of their peppy conversations were struck by instant lightning. When phone lines dropped, they couldn’t even say their goodbyes; the night that followed was their longest and loneliest.

For a journalist like me the night was even more cruel as I tossed around in my bed not knowing what was happening in the world outside. Since all means of communication were blocked there was no way of reaching out to anyone or having matters confirmed.

Being so cut off from the outside world, for the first time in my journalistic career I felt completely helpless. The entire night, as a habit, I kept checking my social media accounts hoping they would refresh, but they didn’t.

Like every other Kashmiri, I too tried to figure out the reason behind such a harsh information blackout but failed to grasp any particular reason. It was unprecedented even by Kashmir standards.

Next morning, on August 5, the Indian Home Minister Amit Shah tabled a bill to abrogate Kashmir’s special status in the country’s parliament; it was passed by a majority. Everything then instantly fell into place and we understood that the blackout was going to be a long one.

To stop people from protesting and journalists from doing their job, streets were sealed off and a strict curfew was put in place. The idea was to cage people both in the virtual as well as in the real world. Also, it has been aimed at stopping the flow of information outside of the Kashmir valley. India was certain that given the ‘iron curtain’ communications blockade in Kashmir, the world would not know what was happening there. But they were wrong.

Within a few days, journalists found innovative ways of sending out their stories. A fellow journalist travelled to New-Delhi, India’s Capital (around 1000 kms away), by-air and handed over his story to his editor personally. It took him two days to do so as streets in Kashmir were deserted and travelling after dark was unsafe.

Another fellow journalist who works for an international media outlet, would stop outside the airport looking for known faces travelling to New Delhi or Mumbai. When he found one, he would hand him a pen drive and a contact number.

In some cases, ‘couriers’ shuttled between Srinagar and Delhi on a daily basis just to pick up pen drives, CD’s, memory cards and more from reporters in Kashmir. To an extent, these innovative ways kept the flow of information and the stories from Kashmir intact.

But without any form of available communication life was completely out of gear. Without access to our mobile phones it took us at least two weeks to learn how to trace people.

It was not easy. I recall a friend of mine travelling to Srinagar from Bijbehara town, around 40 kilometres apart, to meet me. He knew I would be either at the Press Enclave, or at the Kashmir Press Club or at my home. He visited all three spots but couldn’t find me.

Unfortunately, he missed me at the Press Colony by just five minutes. That day, after spending almost an entire day tracing me, he went home. While looking for me he had met half-a-dozen journalists that he thought would know me. He told each one of them to pass on his message if they happened to see me.

For a whole week, whenever I met any of these journalists, they would tell me about my friend’s visit and relay his message. At times the same journalist would repeat the message twice in a day, as we all lost track of time and dates. After the first few days most everybody kept their mobile phones at home since carrying them just felt like a burden. Old-fashioned wristwatches were suddenly back in vogue.

Because of this lack of communication, it took my friend and I over a month to finally meet. In between we had visited each other’s areas at least six times without any luck.

I can only imagine the pain and desperation of a lover who cannot openly leave a message to his beloved, the way we friends do. In some cases, they have rediscovered the age-old art of communication: letter writing. But for a generation like ours that is hooked on the internet, writing an actual letter on a piece of paper may prove a most challenging task.

One fine morning, a friend of mine travelled almost twenty kilometres, skipping a dozen heavily guarded barricades, to reach my home. He put his life at risk just to get a perfect beginning for his first love letter to his beloved, who lives in a posh colony of Srinagar. His sleepless eyes spoke of his desperation. He had never written anything beyond a small text or a WhatsApp message in his life. To even write the first sentence he felt helpless without Google.

In an ideal world, he would have asked Google for sample love letters and worked around one of the five hundred thousand letters generated by the search engine. But there was no Google, or internet. So, a journalist friend like me was his only hope. For the first time in almost a decade I sat down to pen a love letter in his place; it was the most satisfying feeling I had had in a long time.

In front of me I had a lover, desperate to communicate with his beloved, but who couldn’t do so since the Indian government had cut off all his means.

Mostly I am as helpless as most of the people living here. When my grandmother passed away, I was on a reporting assignment, and, although I was only a one-hour drive away, it was impossible for my family to in time convey to me the sad news. When I reached home, she was already buried, and although five hours had passed our close relatives and her friends had not yet been reached by the news; they only came to know several days later, some even months later.

On August 14 the government of India finally gave journalists limited access to telephone and internet services at a private hotel in Srinagar. The facility came to be known as the Media Facilitation Centre (MFC).

For over four hundred local Indian and international journalists operating in Kashmir, there were just four computers with access to the internet and one single mobile phone for making calls. The centre opened at 9 am and shut at 9 pm. In between, journalists struggled to file their stories using a deliberately slowed down internet connection.

In order to make a phone call you had to write your name in a government monitored register, add the organization’s name and phone number (which was not working), and then wait for your turn to make a two-minute call.

A journalist friend of mine, who works for an American newspaper, crossed ten heavily guarded barricades, travelled 15 kilometres, and then waited for over three hours at the MFC just to make a two-minute call to his editor in Delhi. He had to convey a correction in his report that he had filed some days earlier.

With only four computers available for the entire media fraternity in Kashmir there was of course no privacy at all.

I recall how I once punched a wrong password and a fellow journalist, standing over my head waiting for his turn, said in a low voice: “Use your first name and birthday instead.” I was shocked.

But when I looked around, I saw journalists like him desperately waiting in line to use the internet so that they could file their stories. It was like watching a World War II movie where dejected and desperate faces entirely filled the screen. Not a single soul smiled.

As the crowd swelled inside the MFC, some local journalists began calling it the ‘Media Concentration Centre.’ They saw the MFC as a modern-day concentration camp to which all the journalists were herded by the Indian government while also being deprived of an internet facility.

Some journalists believed that every single email sent from the MFC computers was monitored by India – that they would know beforehand who is sending what to which editor. There is of course no way to confirm these allegations.

I started to reserve a whole day in order to file a story, since waiting for my turn to use the internet would at times take hours. To make a phone call I reserved half a day.

The same job would earlier have taken me just five minutes while sitting in an easy chair in a coffee shop.

But like every other unfortunate journalist who worked in Kashmir at this time, I too had to reach the Media Concentration Camp to file my stories.

I recall how journalists would try new tricks to create Wi-Fi connections on the government-provided computers. There was always a threat of getting caught by the officials who entirely monitored the MFC. I remember vividly how I felt the first time after August 5 when I connected my phone with one such Wi-Fi connection. It was a surreal feeling. Within no time my WhatsApp and Facebook messenger got bombarded with messages that people had sent.

I couldn’t reply to any of them as I was not supposed to use the Wi-Fi, and I was doing so by holding my phone under the table. At that moment I felt like a criminal. It did not occur to me that using the internet is my right; shutting it down like that is in fact criminal and illegal.

Once home I sat down without the help of any communication tool to write down my experiences as a journalist while covering the Kashmir conflict. There was no way of reaching out to any sources or calling anyone for help in locating a person. Everything had to be done in the old-fashioned way: by visiting every single place personally.

So, as from August 5, I travelled to far off villages and met with hundreds of people and listened to their stories about how they managed to survive the crackdown. I wanted to write down every single experience I had during these visits.

The following month I would sit every night at my computer and write and at the end of the month it looked perfect. However, when it was almost ready to publish, I made a mistake: I visited the MFC and used a pen drive to download my e-mails. That evening when I used the same pen drive in my own computer, it infected my entire machine. The next morning when I woke up, I saw that my entire data was wiped out – including the piece I had just finished writing.

I realized that this computer virus was my souvenir.